What Does a "Wikipedia Edit" Represent?

no, one guy did not write a third of the site

![Image Fanart of Wikipe-tan, Wikipedia's anime-style mascot, a girl with blue hair and puzzle piece hairclips wearing a Japanese maid outfit. In this image, she's looking smug and passing the reader a piece of paper with "[citation needed]" written on it. The background is a bunch of tesselated [citation needed]s.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!P90Q!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9a486f3b-4683-44f4-8633-ddab813ba54b_680x609.png)

Wikipedia is “the free encyclopedia anyone can edit”. Everyone knows this. There are quite a few things to say about the meaning of some of those words — but everyone knows this. Like most things “everyone knows” about Wikipedia, this is a calm ocean surface above a maelstrom of alien seas.

When 99.repeating% of people interact with Wikipedia, they’re interacting with articles. Maybe you’re looking at the Main Page in class to procrastinate in a way the teacher won’t notice. Maybe you’re reading up on that disease your cousin’s kid has. Maybe you just want to know why beetles are called that. Most people never consider the existence of a Wikipedia outside of articles. Curious kids the way I was might notice a “Talk” tab next to the “Article” one, and click it wondering what they’ll find. This goes down some interesting rabbit holes, but still gets you to only two namespaces.

There are a lot of namespaces.

Wikipedia uses a “namespace” structure, where pages are separated into…Types of Guy based on prefixes. Virtually everything readers see is in “mainspace”, the unnamed ‘namespace zero’. The next most recognizable namespace is Talk, where editors discuss matters relevant to a particular article. To give a real-world example: Dark Archives is in mainspace, while Talk:Dark Archives is in…talkspace.

The next level removed from reader experience is userspace. This includes peoples’ userpages, such as User:Vaticidalprophet. Userspace also offers ‘sandboxes’, scratchpads for a particular editor — commonly drafts for new articles. It’s easy to rack up an absolute ton of userspace edits, through both perfecting your own userpage and writing 20,000 drafts at once. (Once you turn the drafts into real articles, they’re retroactively assigned as mainspace edits, but this assumes a 100% success rate in actually finishing them.)

The next level of abstraction is “projectspace” — prefixed by “Wikipedia:”. These are the metaphorical smoke-filled rooms in which the encyclopedia is made. There’s so much to say about projectspace — deletion discussions, admin elections, rulesets that sprawl like the crunchiest tabletop RPGs — but my example is going to be one of the funniest joke essays of all time, Wikipedia:Please be a giant dick, so we can ban you.

From here, that list of namespaces explodes. Images are in their own namespace. Categories (lists at the bottom of an article) are their own namespace. Templates (think navigation boxes and ‘infoboxes’, the article sidebars) are their own namespace. The list grows ever more obscure and ever further from obvious reader experience; some namespaces would require their own posts to do justice. Every one of these also has their own talk variant, effectively doubling the namespace count.

The “edit” is the basic unit of Wikipedia-interaction. One edit can represent any of the following (this list is not comprehensive):

A huge revamp of an article, springing fully-formed from one’s proverbial pen

A tiny typo fix

Plastering an article with cleanup tags in lieu of fixing it yourself

Reverting vandalism (troll edits)

Uploading an image that may or may not actually make it into an article

Adding or removing an article from a category

Adding 200 userboxes to your userpage

Fixing the formatting after you screwed up adding 200 userboxes

Beginning a review in one of Wikipedia’s peer review processes

Arguing about a review in one of Wikipedia’s peer review processes

Tweaking a template’s formatting

Informing some guy you’ve just nominated his article for deletion

Arguing with the guy who just nominated your article for deletion

Chilling out on your friend’s user talk

Making talk pages for things that really don’t need talk pages

Shitposting on the dramaboards

(“Wikipedia has dramaboards?” Like you wouldn’t believe.)

Readers tend to think of #1, and occasionally #2, but all of these make up somebody’s “edit count”.

Intuitively, some of these are more productive in terms of Building the Encyclopedia than others. This is one of those intuitions that’s obvious when you’re seeing it on the abstract-world-of-forms level, but gets slippery when you formalize it.

Let’s talk about a fun example: reverting vandalism. Vandalism is an umbrella term for all sorts of “intentionally antiproductive edits without redeeming qualities”, ranging from twelve-year-olds replacing articles with “U ALL SUCK COCKS” to sophisticated and wide-ranging attempts to undermine the project. This all sounds very bad, so we have a lot of systems set up to prevent and cure it. Some of these systems are bots, such as ClueBot NG, which reverts the lowest-effort “U ALL SUCK COCKS” vandalism the moment it strikes. Most of them are people.

Wikipedia’s recruitment systems for anti-vandalism editors are…a little intense. They appeal to the sort of people who look at the words “Counter-Vandalism Unit” and either don’t realize that it’s a reference to “Counter-Terrorism Unit” or think that sounds based. They appeal to people who look at “This user despises vandalism and reverts it with extreme pride” userboxen1 and think that sounds cool and like something they want to put on their userpage.

This is to say that editors primarily focused on antivandalism tend to be quite young, maybe were recently vandals themselves, and maybe tend to see things from a bit of a recreational-FPS-MMO perspective. They tend to take their jobs very seriously, understandably, because it’s presented to them in a very serious way. They don’t always feel comfortable in any other way they can contribute to Wikipedia; the idea of writing articles from scratch or redoing existing ones seems unapproachable. The extreme version of this is the metonymical “teenage hugglebot” — someone button-mashing Huggle, Wikipedia’s most powerful antivandalism tool, and treating it more as a game of who can revert fastest than actually looking at the edits.

This can get…unproductive. Notorious examples tend to revolve around unregistered editors. Wikipedia lets people edit regardless of whether they sign up for an account or not, but unregistered editing has a nasty coordination problem:

A number of respected and recognizable editors choose, for various reasons, to edit under an IP address rather than an account.2 They are a minority compared to the IPs who…confirm the stereotype, if you will. For an antivandalism editor, who sees more “bad IPs” than your average Wikipedian, it gets even harder to consider the “good IP” concept. This feedback-loops with a tendency for antivandals to not always be the most nuanced people on the project.

I once saw a well-known IP editor make an edit to a biography. Like many of our biographies, this article was on a low-profile living person, someone notable for his contributions to a field but not in any way a public figure. For some insane reason, it mentioned the names of his children and the street he lived on. Our anonymous friend removed those things from the article, as justified both by Wikipedia’s rules and by basic human dignity. Shortly after, someone came along and Huggle-reverted it with the edit summary “Unexplained content removal”, dropping a strongly-worded template-letter on our friend’s user talk.

This happens all the damn time.

Antivandals tend to get very high edit counts, even the ones whose edits are disproportionately like that. Huggle and other “semi-automated” tools allow you to rack up edits far faster than you could manually reverting vandalism, let alone doing slower things like writing a whole article.

Any given act of antivandalism also requires multiple edits; not only do you need to revert the offending edit, you generally need to inform the vandal you’ve done so. We have a whole suite of standardized warnings for every way you could possibly screw up, including ones you frankly shouldn’t use standardized warnings for. Not only does this provide some sort of evidence you’re theoretically communicating with someone rather than reverting blindly, it’s also enough to stop a lot of low-effort vandalism; many vandals are just bored kids who want to see what will happen, and have the fear of God struck into them when they learn someone’s paying attention. If someone persists, you eventually report them to AIV, where a passing admin either blocks them or yells at you for calling this obviously-not-vandalism “vandalism”.3 Consider someone doing this whole cycle several times a day, and you can see how antivandals rack up a lot of edits.

Wikipedia needs antivandals. ClueBot can’t get everything, and what it misses is often the most important things to catch; surreptitious changes more subtle than “U ALL SUCK COCKS” can make for serious errors on a large scale. But if you see Wikipedia in terms of edit count, then a worse-than-ClueBot antivandal (50k edits) is a “more valuable editor” than a prolific writer of quality articles (15k edits). You can get your edit count much higher through the former than the latter.

Huggle is nice, but AutoWikiBrowser is the big gun.

AutoWikiBrowser, generally known as AWB, is a desktop browser specialized for editing Wikipedia at high speed. Almost all images of it on Commons4 are from the late 2000s and look it, but I was unsurprised to find a screenshot from 2019 that looked exactly the same:

As the screenshot shows, a common use of AWB is fixing easily-made typos. The average editor might fix such typos as he comes across them, but AWB allows you to power through thousands of pages at once. It’s not limited to articles, either — you can fix typos all across Wikipedia. (Don’t use AWB to fix typos in other people’s comments.) Other widespread uses of AWB include:

Implementing general fixes, a number of mostly-minor, sometimes-hilariously-not-minor tweaks

Playing with categories, assigning/reassigning articles to categories at scale

Creating certain types of pages, like talk pages

AWB is pretty cool. By fixing thousands of typos at once, we can significantly increase productivity and reroute editor attention to bigger problems. (In practice, sometimes those bigger problems are “1000 articles have new typos because someone screwed up an AWB run”, but not usually.) It does, however, completely break the relationship between edit counts and editor experience. Though AWB is only available to people whose accounts have been approved for it (anyone else will be blocked from logging into the browser), it doesn’t necessarily require the highest bar of activity. Once you have it, you can easily see your edit count soar into the high five or even six figures.

Between Huggle and AWB, some people get extremely high edit counts. XTools, which lets you check details of someone’s edit history, breaks for anyone with more than 650,000 edits. There’s a reason the threshold is that high. There are still people past that threshold.

So, let’s try to measure quality, not quantity. How do you measure quality?

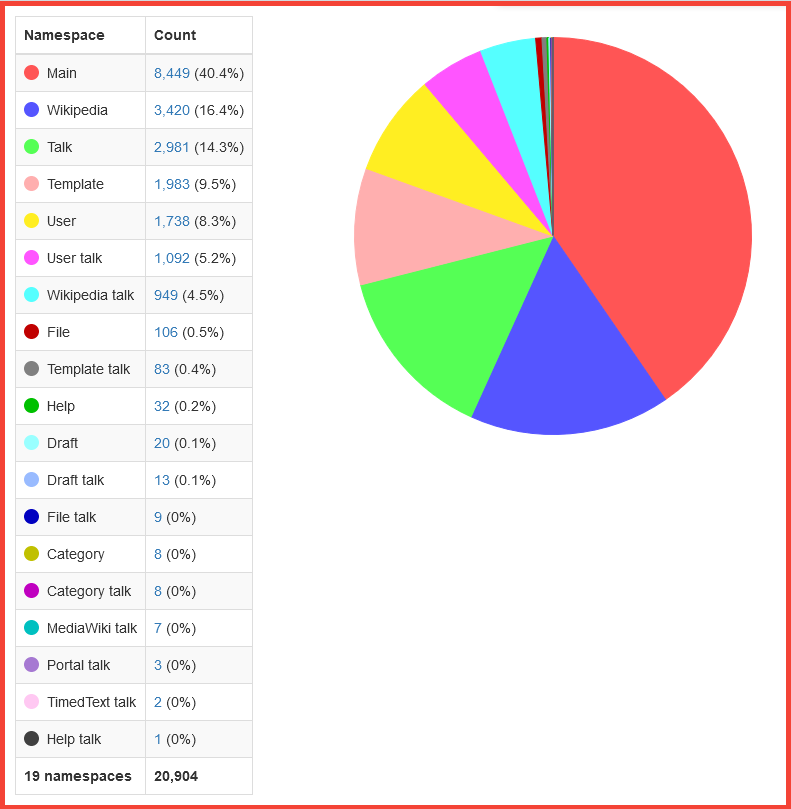

One technique is to check what namespaces someone edits in. XTools has a handy chart. Here’s mine:

You can get some loose impressions of people from their namespace distribution. Classic antivandals will have roughly-equal main and user talk, with few edits elsewhere. People whose edits are overwhelmingly somewhere like filespace, templatespace, or categoryspace are definitely in a particular niche. Someone with very little red5 on their chart is barely doing anything with articles. As a loose rule of thumb, people want red/mainspace to be at least a solid plurality, unless someone has a good excuse like focusing on particularly advanced technical skills.

But once you’re past “some guy with literally 80% projectspace edits” (I have seen these charts), how close does this get you to things you want to measure?

Well, my mainspace percentage is currently 40%. It’s been lower. I have months where it averaged as low as 20%. I think I count as a content editor, probably:

(I’m eventually going to have to write the “how Wikipedia’s peer review processes work” post, I think.)

Some people use >50% as their heuristic mainspace threshold. This excludes someone like me from being a “content editor”, which is rarely a desired outcome. I know people with more impressive article contribution records than myself, who have even lower mainspace percentages. There is a lot of Wikipedia out there, and you can get more edits “repeatedly correcting your grammatical errors in a talk page post” than “revamping a significant portion of an article”.

In turn, high mainspace percentages aren’t necessarily a sign someone is writing articles with all those edits. AWB use will generally get a high mainspace percentage, if someone is using it primarily for typo-fixing and article-related genfixes. Again, these edits are meaningful and important, but they’re not what comes to mind when non-editors hear that someone has made “X many Wikipedia edits”.

Other proxies for “mainspace contribution” include (not comprehensive):

How many articles has this editor created?

How many articles that this editor is the primary contributor to have successfully undergone peer review processes?

How many articles that this editor is the primary contributor to have gone through other processes with some quality threshold (e.g. appearing on the main page)?

How many reviews has this editor done at such processes?

All of these have their merits and flaws.

The first is the most transparent to readers, and, in many ways, the worst. I’ve written about this before; editors tend to parse “writing articles” and “creating articles” as fairly similar, with serious consequences. Articles being created today tend by definition to be articles no one else created for twenty-three years, meaning they tend to be either pop culture or very niche. The fruit still hangs lower than you think if you have anything approximating expertise on any topic, but judging people by how many articles they’ve made prioritizes mass-creation drama above all.

Wikipedia’s peer review processes, meanwhile, have the upside of requiring some sort of quality. To avoid making this the post about how they work: Wikipedia has a two-tiered peer review system, with “Good Articles” being reviewed to a moderately high standard by a single reviewer, and “Featured Articles” (seen in “Today’s featured article” on the main page) being reviewed to an exacting standard by at least three people and sometimes far more. Someone with a lot of GAs and particularly FAs is evidently doing something to benefit the encyclopedia.

…usually.

GA’s “Reviewer Roulette” structure masks deep chasms in interpretation of the criteria (I am holding myself back from writing several thousand words about “minimum length for a Good Article” disagreements). FA is more consistent — “someone has multiple FAs” is the best benchmark you’re getting for this — but has an unavoidable rate of both type I and type II errors. FAs are also rare, comprising about one in a thousand articles, and GAs are still less than 1% of the project. Very few editors have any FAs, let alone multiple.

There are in turn serious arguments that the FA/GA structure is fundamentally flawed. Many quality-assessed articles are on obscure subjects, sparking vicious debate about whether and how badly this is a misuse of editor resources.6 Many editors are uninterested in engaging with the processes at all, despite writing articles that could pass them; many are so engaged that they insist on dragging substandard articles through, and, well, you can get away with that at GA for a while.

Also, readers have never heard of any of these, which makes it a bit difficult to use them as reader-comprehensible benchmarks.

In turn, if an editor is benefitting from these processes, it’s good for them to do reviews themselves. This is a great metric of how involved someone is in improving articles! Also, reviews aren’t done in mainspace, so lol have fun with your namespace percentages.

Finally, there are a number of article recognition processes outside of the peer review framework. Most notably, articles only need to pass basic “not an embarrassment to the project, hopefully” quality standards to appear on the main page in “In the news”, “On this day”, and “Did you know”. ITN and OTD have obvious additional restrictions, but DYK is open to any article, as long as it was either created, expanded fivefold, or brought to Good Article status in the past seven days. Accordingly, a lot of article-focused editors are big fans of DYK.

But if someone is making a lot of “barely DYK-appropriate” articles…well, how much good are they doing? There are editors who specialize in DYK and rarely touch any other content process. They tend to be controversial. They are sometimes controversial enough to cause massive shitstorms that occupy the entire project for months on end. I’m a big fan of DYK, and for many reasons I don’t intend to write the “why DYK is controversial” post here, but…it’s not an uncontroversial metric of how many decent articles someone has written. Plus, given that non-GA articles at DYK need to have been either nonexistent or very short before, it ties into the same “rewarding obscure subjects” problem.

Wikipedians know about these problems. But Wikipedians, talking about what non-Wikipedians understand, are exemplars of this problem:

We have a list of editors by number of edits, so it must be a big deal, right? Ignore that four of the top ten are currently or formerly banned.

Once someone’s edit count gets really high — somewhere well into six figures — its relationship with “contributions that non-Wikipedians understand” inverts. For everyone past 10-15k or so it’s already a zero correlation, but extremely high edit counts denote people focused on semi-automated editing. Again, this doesn’t mean “people who don’t do things of value” — high-volume editors are doing things of value — but a non-Wikipedian, intuiting “edits” as a direct measure of article contribution, will make deeply erroneous assumptions.

Exceptionally high edit counts — those approaching or past the XTools threshold — tend to represent an interest in categories. Categories are the boxed lists of relevant over-topics at the end of articles, like so:

Categories are important. They genuinely serve a useful navigational role — I can tell you, first-hand, I looked at categories long before I was an editor. They also draw…how do you say this…people who, even by Wikipedia standards, are really invested in “making sure things are all categorized in the Objectively Correct way”. This is one reason why we keep banning people with high edit counts.

Categories lend themselves well to mass automated edits. If you need to add or remove a bunch of articles in a category, might as well script it. Even my setup, as shown there, involves a lot of category-related automation, and I don’t care about categories past the minimum of “I need to put my new articles in them so they don’t get tagged {{uncategorized}}”. Accordingly, editors interested in categories can rack up astronomical numbers of tool-assisted edits.

When people hear that someone has “a hundred thousand” or “a million” or, oh, “over five million Wikipedia edits”, they don’t tend to think “oh, that guy is doing a bunch of automated edits involving categories”. They think “this guy must have written an absolute ton of what I’m reading on Wikipedia”. The former tends to be more accurate.

This has real-world implications. Wikipedia interests people. It’s one of the most important sites of the modern internet, and there’s enough awareness that it’s “written by people” to draw interest, but it’s poorly-understood. Anything that promises to increase people’s awareness of Wikipedia gets popular. Accordingly, people with high edit counts tend to draw media attention.

The current and former “most active editors” both have Wikipedia articles. Both earned those articles by receiving prolific media attention. The former has repeatedly been called “the man who wrote a third of Wikipedia” by sources that should know better. This is not a criticism of him — he’s a great guy. But he’s not one of “the 25 most influential people on the internet”, which Time goddamn Magazine called him, and which we put in his article that gets 10,000 views a month from people wanting to learn about “the man who wrote a third of Wikipedia”. I can think of Wikipedians I might call one of “the most influential people on the internet”. I would certainly call the Wikipedia Hivemind that.7 But edit count is not the relevant axis, and we’re bad at explaining why.

This is painful, because we’re dragging hardcore attention onto private individuals. I have seen people write fucked up awful conspiracy theories about these guys. You can see why this happens, if you think they wrote a third of Wikipedia! There’s a lot of Wikipedia I’d be criticising if a third of the whole thing was written by one guy. But it’s pretty vile to represent a single private citizen as The Guy To Blame for a huge morass of complex opinions and the uneasy truce brokered between them. By being unclear about what “edit counts” represent, we’re functionally doing this, turning innocents into lightning rods for everyone’s problems with Wikipedia.

We’re also missing the opportunity to talk about what a “Wikipedia edit” is, and the many complex things that go into creating the project. It’s a deep rabbit hole of competing factions, at once more and less cryptic than it seems. (A similar problem to this one: “the government/CIA is manipulating Wikipedia”, based on “an IP address connected to a government organization has edited Wikipedia”.) I think it’s important both for its own sake and for other sakes — including “giving Wikipedia any chance of surviving the next few years” — for people to understand more about the project. It’s a strange, beautiful, impossible place, “the free encyclopedia anyone can edit”, for many values of those words. We don’t do it justice.

This is the correct plural (see also “navboxen”, “infoboxen”). It’s the fault of German Wikipedia. A lot of things are the fault of German Wikipedia.

Unregistered editors are identified by their IP address, which is one of those interesting “Wikipedia is a website from 2001 with a lot of plastic surgery” things. They’re habitually called “IP editors” or “IPs” for this reason. Because you can’t actually run a website in the 2020s with public IP addresses and be compliant with whatever the EU is doing today, this is slowly changing. It will probably be untrue just a few months from publication.

“Vandalism” is narrowly defined. Any good-faith edit, no matter how bad, is not vandalism. Some complain that AIV is “the place people report IPs for editing about cartoons in a way they don’t like”. This feedback-loops with the tendency for many antivandals to be specialized and have fairly little experience with writing articles; the distinction between “a weird and maybe not-very-good edit” and “vandalism” is trickier to make when you’ve built less than you’ve torn down.

For short purposes, “Wikipedia’s image host”. They hate being called that.

“Darkest brown” in colourblind, I think. Heuristically, almost everyone has more red/mainspace than anything else, so “look for the largest brown one” almost always works.

I can’t do justice to this in this post. It’s complicated as hell, and you really need to read between the lines in TCO’s presentation.

“Be careful what you wish for.” I like Wikipedia and I like Wikipedians, but any Wikipedian who might be this has done both good and harm. This is also true of the-hivemind-of-Wikipedians, including my own place in it.

1. omg didn't know "userboxen" was a german thing

2. ok now i'm so curious about your DYK hot takes............

3. you should mention in a future newsletter how among the antivandalism teens (bless their hearts) there is the literal materials scientist called materalscientist who pivoted from writing about materials science to going sicko mode with antivandalism and has not slowed down for years, eluding the fast burnout that plagues most of the antivandal patrollers, and still managing to get materials science research published in journals

4. shoutout to steven for writing a third of wikipedia!

Are you sure ‘navboxen’ etc. is from German wikipedia, not 90s ‘hacker’ lingo as listed in eg ‘the jargon file,’ where boxen is the (intentionally un-English) plural for a ‘box’ in the sense of a computer (eg i have a mac box, a windows box, and a linux box, so three boxen)?

jargon file entry: http://catb.org/jargon/html/B/boxen.html

hacker usage on urban dictionary: https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=boxen

(also this is a really interesting article, thank you for writing it!)