On Not Being Colourblind

the accident of trichromacy, the lessons of dichromacy

“How common is autism?” is an open question. Prevalence estimates ramp up every year. Some diagnosis is wrong, but that only takes you so far — we’re clearly getting better at spotting autistic people.

There has to be a ceiling to how common autism can be, because past a certain point, you’d see a much more autistic society than the one that exists. Different societies clearly have different baseline-autism-assumptions (in intercultural communication, this is called “high-context” versus “low-context”), but even low-context cultures seem high-context to most autistic people.

How common can something be while still existing in a society to which it is alien?

“Red-green colourblindness” — an unnatural category that includes both protan (mutated “red” cone) and deutan (mutated “green” cone) people, whose colour vision is more alike than the different causes would suggest — is thought to occur in around one in twelve men of European descent. It’s rarer in other ethnicities, but not remarkably so. It’s rarer in women, by nature of its X-linked recessive pattern, but about one in two hundred Euro-descent women are colourblind — a prevalence high enough it would make for one of the most common congenital disorders by itself. We think of it as vanishingly rare because we compare it to the male prevalence.

Medicine has, damnably, fallen out of the habit of detailed and personal case studies. You can hem and haw all you want about evidence bases, but come on, this is a loss. (You realize just how bad a loss it is when you’re writing a literature review of case reports.) An exemplar of what we lost is John Dalton’s 1794 Extraordinary Facts Relating to the Vision of Colours: With Observations — deuteranopia described, in intricate detail, by a deuteranope. It was the first ever account of colourblindness, a concept previously considered only in “is your red the same as my red?” theory. Dalton declared, in fact, that his red was no one else’s:

“I have seen specimens of crimson, claret, and mud, which were very nearly alike. Crimson has a grave appearance, being the reverse of every shewy and splendid colour…Pink seems to be composed of nine parts of light blue, and one of red, or some colour which has no other effect than to make the light blue appear dull and faded a little. Pink and light blue therefore compared together, are to be distinguished no otherwise than as a splendid colour from one that has lost a little of its splendour…Blood appears to me red; but it differs much from the articles mentioned above. It is much more dull, and to me is not unlike that colour called bottle-green. Stockings spotted with blood or with dirt would scarcely be distinguishable.”

—Dalton, 1794, pp. 32-33

This is striking, when you think about it. Red, to the trichromat, is the colour of splendour. It is as intense as colours get, every emotion cranked as far as it goes, the representative of blood and fire, rage and love. Yet to the colourblind this is precisely reversed; red becomes mud, a dull and faded colour. Blood on a battlefield flows seamlessly into the dirt. This is not the experience of a vanishing minority — it is, to make a decidedly apropos comparison, more common than red hair.

We don’t think about colourblindness much. In fact, we consistently don’t think about colourblindness. It exists wholly outside our World-Possibilities. To a trichromat, red and green are exceptionally contrasting. We intuitively use them when we need contrast; we paint maps in them, put them on the opposites of an artistic “colour wheel”, festoon everything in them for the whole damn month of December.

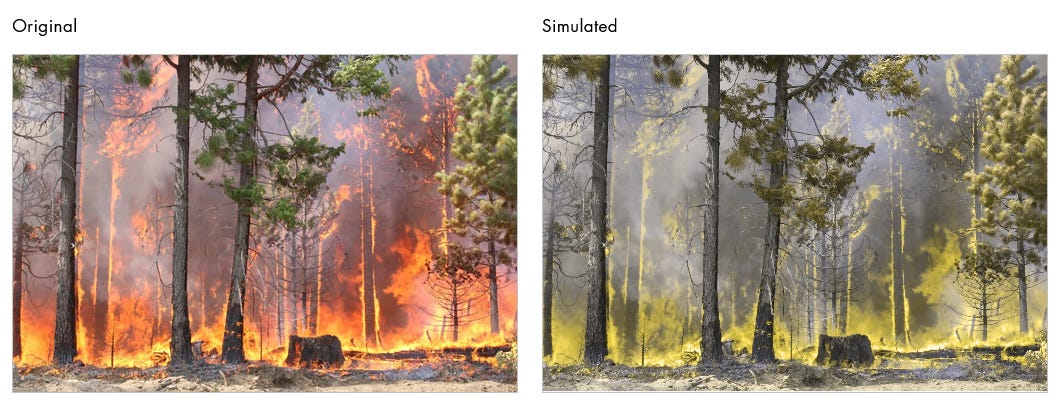

We talk about red and green in ways that, to protans and deutans, must sound consistently bizarre. Red — the most muddled and uninspiring of all colours, to them — is the very distillation of passion and intensity. Green, barely distinguishable, represents undisturbed nature. To extreme protanopes, the leaves burning in a forest fire occupy the same space as the fires licking at them:

As our colours have gotten “better” — as we have produced more intense pigments than Nature gifted us — the discrepancy only worsens. We make household objects in colours once seen only in the sweetest berries. We fill our cities with neon lights, signs glimmering and flickering and calling. We dress ourselves in colour and expect people to draw conclusions about us based on subtle details; the “woman in the red dress” is a thousand stories drawing on one archetype’s power.

The red dress represents vibrancy, sensuality, untethered appetites. But to one in twelve men, it becomes the opposite: a shrinking, unassuming colour.

I’m always fascinated to learn someone is colourblind. It feels like being let in on a secret — on the knowledge that someone else’s world is fundamentally unlike yours.

You can run colourblindness filters, but I’m skeptical that they get you to the exact same place true colourblindness would. The reverse — granting true trichromacy to a dichromat or anomalous trichromat — is an even less bridgeable gap (wacky glasses aside). Even filtered images don’t get you to the real experience, the way the whole world looks when you look up at it. I know what my green eyes look like, and the way the skin over my palms is so pale as to be practically translucent, turning them a near-reddish pink. I have no way of knowing what anyone I meet thinks they look like.

If filters have any accuracy to them, they imply some very interesting things indeed. Photographs of people placed through a protanopia filter acquire a sickly green cast. The effect remains consistent across all skintones, giving the unshakeable sense of walking corpses. Deuteranopia, milder than protanopia, lacks this extreme effect — but there are still uncanny valley consequences, if you’re used to looking at people as a trichromat. Lips and nails, where your blood shows through your skin most, look dull and washed-out. The impression is that everyone is slightly ill at all times.

This can’t be taken at face value; the resemblance between such filters and reality is clearly well south of 100%, and these descriptions apply to the -anopia variants, not the more common and subtle -anomaly variants. But it’s disconcerting, if you’re used to trichromacy. Your hindbrain lights up, tells you something is wrong.

Many of us go through life seeing people differently, in a not-literally-visual sense. We read different implications into facial expressions, or none at all. We pay attention to different features. We value certain character traits more or less. What does it mean to see people differently the way a colourblind person does? Does your subconscious react differently to the undertones in someone’s complexion, telling you if they’re sick or healthy?

I’m writing from a living room with large glass sliding doors leading into the backyard. The morning sun highlights the lawn in its vivid greens. The red blankets spread across the couch are a little muted; the room doesn’t quite face due East, but enough outdoor light is coming directly through for the indoors to seem dimmer by comparison. On a bookshelf, a “Season’s Greetings” card from December is still perched, red flowers offset against a green background. A tablecloth beneath my laptop is set in crimson-red patterns. The world looks different to me, in some ways, but in all these ways it looks the same. I take this for granted. I shouldn’t.

Red-green colourblindness wasn’t described until the last years of the 18th century, despite affecting one in twelve men. Thousands who lived and died between the dawn of man and the 19th century must have unhesitatingly assumed their colours were the colours of everyone else. It wasn’t until this remarkably recent chapter that any of them thought they weren’t.

Dalton, in his monograph, found it a strikingly common secret. His own brother saw the same way. The only description he could find of colourblindness before him was a case report of a single family — but quite a few brothers. He routinely brought up the subject to friends, acquaintances, and students, finding a substantial minority of all three saw the way he saw. None of them had ever thought anything remarkable about it, and assumed any confusion was on the part of others:

“They, like all the rest of us, were not aware of their actually seeing colours different from other people; but imagined there was great perplexity in the names ascribed to particular colours.”

—Dalton, 1794, p. 39

One must imagine many of the other people Dalton mentioned this to were shocked.

Colourblindness was, apparently, not a remarkable day-to-day trait until the 19th century. Dalton mentioned that he seemed to see colours better by candlelight or moonlight, but the nascent electric lighting made him as colourblind as full day. Industrialization made colourblindness potentially deadly; railway signalmen and sailors on commercial ships could cause disastrous crashes if they were unknowingly colourblind. We didn’t hesitate to make red and green important — after all, they were some of the most contrasting colours to most of us. We didn’t realize just how often this was reversed.

You’d think something affecting just over 4% of the population would make a bigger mark. It’s remarkable just how absent it is. Not until it became a risk to life and limb did anyone think it at all strange that red could be “the reverse of every shewy and splendid colour”. Today, now that colourblindness is visible at all hours and impacts much more of someone’s day-to-day life, it still barely registers. The colour associations of red and green are too deep. Except for more than one in every twenty-five people.

How different can large groups of people be? Different enough no one notices that more than 1 in 25 people have a completely, fundamentally reversed idea of colours.

Trichromacy is the exception, not the rule. We speak of “anomalous trichromacy” when describing the milder forms of colourblindness, but trichromacy itself is anomalous amongst mammals.

Almost all mammals are dichromats. The ancestral state of mammals is nocturnal, and nocturnalism doesn’t demand the most sensitive colour vision. Most exceptions are outright monochromats who lack any colour vision, which is vanishingly rare in humans. Intriguingly, this includes cetaceans, who count amongst their number the strongest candidate for another sapient species.

Mammalian trichromacy is exclusive to primates and marsupials, and not constant in either. Catarrhine primates evolved trichromacy as a weird kludge on the X chromosome, easily the second least convenient chromosome to work from if you want a gene to be consistent. As catarrhines with delusions of grandeur, we ended up with the consequences.

But dichromacy itself is an outlier. Vertebrates are, by default, tetrachromats.

Three is not the optimal number of colour vision cones. It’s the number we lucked into. There is something else just beneath; in another world, we would route the colours another way yet again. We might scoff at the way we think of red as “shewy and splendid”, pulling apart the multitude of reds we place under this pitiful umbrella. We might look at the lawn before me and see a kaleidoscope beneath the sun, flattened by my trichromat eyes into a sea of green. We might look at the rainbow and see not God’s warning, but his face.

The concept of human tetrachromacy enraptures people. On paper, women who carry a deuteranomalous or protanomalous gene should be tetrachromats. Most evidence we have of this suggests that if they’re tetrachromats at all, they aren’t so in any practically meaningful sense — they don’t see any more colours. But some might.

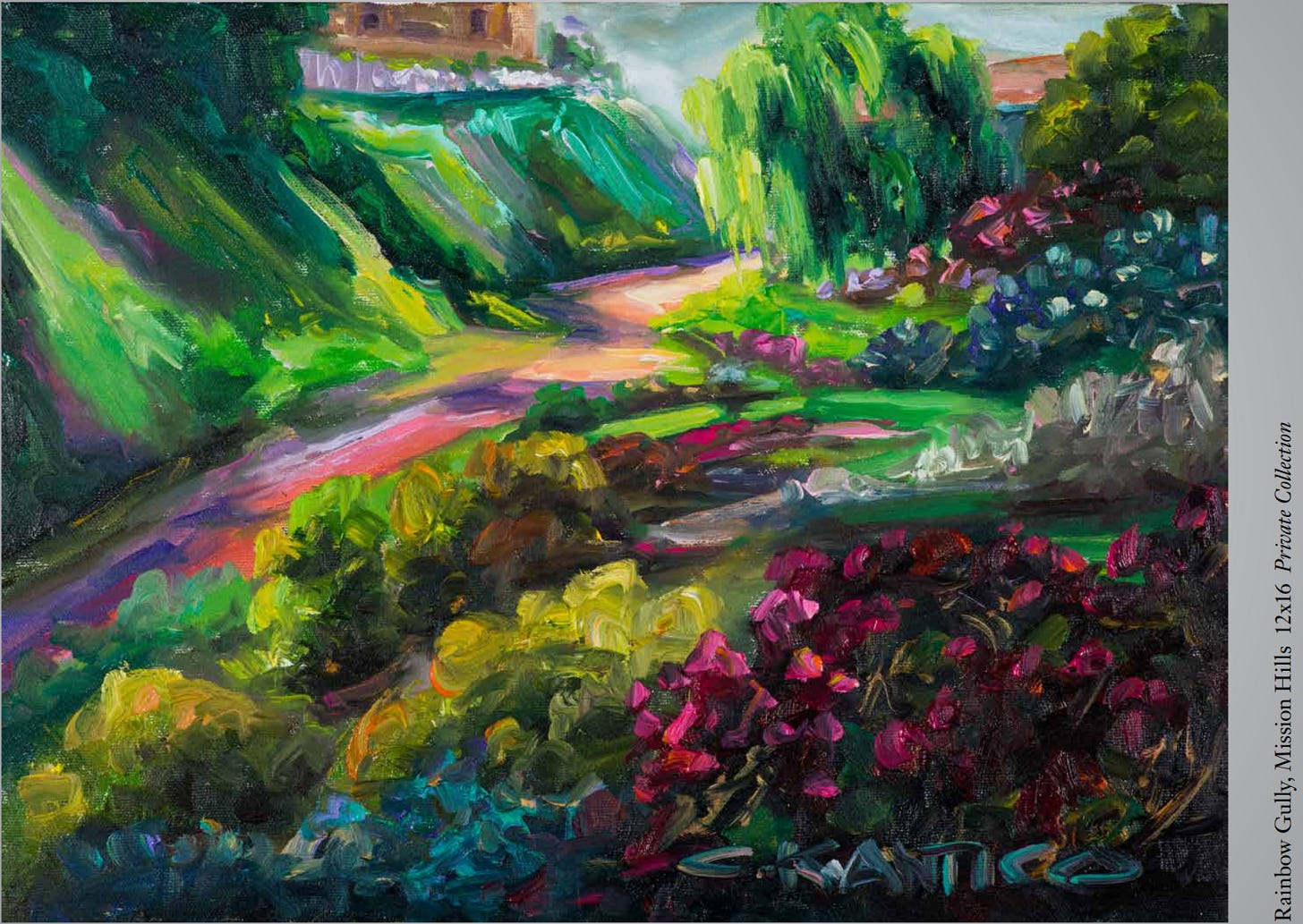

Human tetrachromacy, when we can find any evidence of it at all, might be a letdown. Almost all reported cases seem questionably useful. Only one of the many, many people tested for tetrachromacy seems to see more colours in what might be the sense we think of. She makes pretty cool paintings:

She describes these paintings as “exactly what I see”. It’s a little difficult to figure out what this means. Definitionally, when she picks out a certain colour of paint, she should see something as different from what I do as a dichromat does. When I look at this, what am I seeing? By all rights, it should be as pale an imitation for me as this:

But…I can look at it, and I can think I see something. In a metaphorical sense, I completely understand what she means when she talks about her lack of artistic license:

Until 10 years ago, Antico says, “I didn’t know I was not experiencing the world like other people were. For me, the world was just really very colourful. It’s kind of like, you don’t know you’re a zebra unless you’re not a zebra.”

As a child growing up in Sydney, Antico says she was always “a little bit out of the box” – dying her hair with bright colours and choosing emerald-green carpet and black and lime green curtains for her bedroom. Fascinated with nature, she’d often disappear for an entire day into the land around a nearby golf course.

“I always felt like I was living in a very magical world. I know children say that, but for me, it was like everything was hyper-wonderful, hyper-different. I was always exploring into nature, delving and trying to see the intricacies, because I’d see so much more detail in everything. Someone else might look at a leaf or a petal on a flower, but for me, it was like a compulsion to really understand it, really see it, and sometimes spend a lot of time on it. And I just wanted to paint and portray everything that I was seeing.”

If Antico’s vision is true tetrachromacy, that’s all true. If it’s something else interesting — some unusual ability to pick out details, say — it’s still all true. It’s still something she’s outside population norms on, but in a way where you can go much of your life and never realize.

I want to see her paintings like she sees them. I see a lot of wonder in the world other people never seem to; I want to show it all to them. When I run into someone else, I wish they could return the favour.

Deuteranomalous people can see more colours than other trichromats, under some circumstances. Descriptions of this sound strikingly like descriptions of the double-empathy problem:

The question of why colourblindness is so common tends to rest on this. Colourblindness is not a unitary ‘deficiency’. In the environment of evolutionary adaptedness, it might help one see through camouflage, spotting predators or food sources that no one else could. You don’t get to 8% by accident.

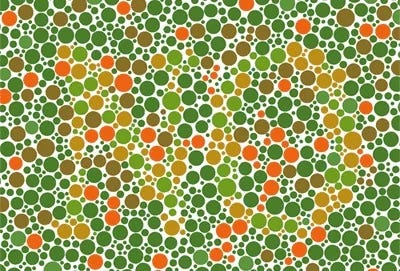

There are such things as “reversed colourblindness tests”. It is weirdly hard to find images online that can both be parsed by simple colourblindness simulators and aren’t at least semi-visible to someone with normal colour vision. If you can discern hues okay, you can probably get the gist of this one:

As I understand it, it should pop out far more clearly to someone in the red-green colourblindness spectrum. I like the concept of this. It’s a reversal of fortune, a demonstration of the complexity involved in proclaiming something “deficient”. You don’t get to 8% by accident.

Here I’m in the 92%. For some unusual worldviews, I’m in the minority — the 2%, or 4%, or 5%, or who-the-hell-knows%. I get to look out my eyes and be confident other people see what I see. I don’t have that confidence for some things.

Colourblindness has been with us forever, a total restructure of one’s worldview. But we only identified it in the last couple centuries. It has obvious deficiencies in a society structured around not having it, but strange and complex upsides, and works very well for many other species. The step up that we consider “normal colour vision” is a descriptive normal, worse than that of most vertebrates. There is a lot about our colloquial understandings of colour that require an absence of colourblindness; there is a lot about the world that disputes this absence at all turns.

Do you ever think about how you’d see through another person’s eyes?

![Bosten et al. (2005): "MDS studies of anomalous trichromats have, however, always had a phenotypic bias: stimuli have been selected to be discriminable for the normal observer and the anomalous space has typically been found to be contracted compared to the normal. Such results reinforce the categorization of anomalous trichromats as ‘color deficient’, but this represents the viewpoint of the majority phenotype. Because anomalous observers have a different set of retinal photopigments from normal, there exist pairs of natural stimuli that appear distinct to them but are indistinguishable (‘metameric’) for the normal [8]: such pairs produce the same triplet of photon catches in the cones of the normal eye but distinguishable triplets in the anomalous eye. We designed an MDS test that favors the minority phenotype of deuteranomaly." Bosten et al. (2005): "MDS studies of anomalous trichromats have, however, always had a phenotypic bias: stimuli have been selected to be discriminable for the normal observer and the anomalous space has typically been found to be contracted compared to the normal. Such results reinforce the categorization of anomalous trichromats as ‘color deficient’, but this represents the viewpoint of the majority phenotype. Because anomalous observers have a different set of retinal photopigments from normal, there exist pairs of natural stimuli that appear distinct to them but are indistinguishable (‘metameric’) for the normal [8]: such pairs produce the same triplet of photon catches in the cones of the normal eye but distinguishable triplets in the anomalous eye. We designed an MDS test that favors the minority phenotype of deuteranomaly."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!stWP!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb5053905-24b6-41ae-9177-eb31e245d553_675x268.png)

I have protanomaly and I approve (like) this message.

> It is weirdly hard to find images online that can both be parsed by simple colourblindness simulators and aren’t at least semi-visible to someone with normal colour vision.

The reason you can't find these images online because they can't be represented in RGB. It requires a more specific spectrum than computer screens are capable of producing.