Wikipedia is one of the most important sites of the modern internet, possibly one of the most important inventions in history, a democratization of knowledge on the level of the printing press. Nonetheless, it’s poorly understood by most of its readers. There is a broad but nonspecific awareness that “anyone can edit”, and a slightly narrower awareness that troll edits (“vandalism”, in the native tongue) are quickly reverted. Some people are loosely aware of the Free Culture allegiance, or the byzantine inner workings. Ultimately, people use Wikipedia constantly — for school, work, and leisure — but see only a fraction of it, with no clue how the sausage is made. Things like Depths of Wikipedia, with its three-quarters of a million followers, demonstrate that a huge and unfilled demand exists to know more about what Wikipedia is.

Because Wikipedia isn’t well-understood by the general population, misconceptions frequently rise from the subjects of its articles in particular. People think their Wikipedia “profiles” are something they can gain control over, or something that people are paid to edit, or something vaguely under the auspice of the Wikimedia Foundation. One occasional result of this is that an article subject, seeing edits they don’t like, demands to the WMF that the editors “harrassing” them be stopped — or even doxxed.

The subjects of two articles recently made such a complaint. It’s not particularly relevant who they are; minor politicians in an American state I’ve never been to, people formally eligible for articles on the basis of their station but rarely considered important enough by editors to get them. One of the people they demand doxxed is the creator of their articles. They reportedly have “deep concerns” that the same person made both articles, and think this is part of some harrassment campaign.

Both subjects happen to be women of colour. When I saw that, I knew exactly what happened.

Wikipedia does not grow the way it once grew; stats like the number of editors active at any given time have been variably sliding between ‘flat’ and ‘declining’ since 2007. Still it grows, it thrives, it catalogues new notable subjects and ones we missed the first twenty years. (Shockingly many.) Perhaps the single most active project to develop out of Modern Wikipedia is Women in Red.

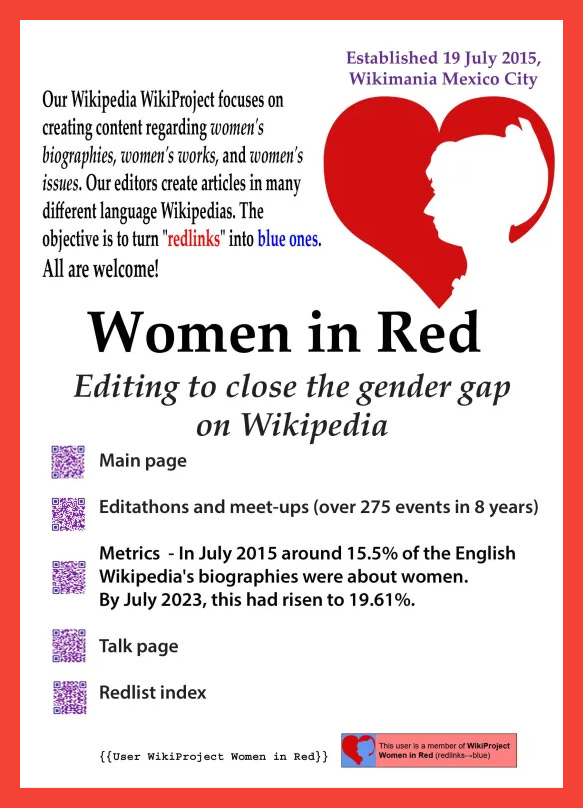

About a third of all Wikipedia’s articles are biographies, mostly Biographies of Living Persons (BLPs) — one of the truest biases on the project is “recency bias”, a tendency to reflect what people are doing and not what they have done, such that the hundred billion dead are less chronicled than the eight billion living. When Women in Red was founded in 2015, around 15% of all biographies on the project were of women; today it is around 20%. (For comparison, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is 17% women post-1900. Almost all general biographical dictionaries are similar.)

Women in Red (WiR) holds the philosophy that this gap is 1. an injustice and 2. a solvable one. Their mission statement is to create articles about women until(?) the proportion reaches parity. As can be extrapolated from the statistics, plenty of active editors have some interest in this ideal — I’m sympathetic towards the thought process myself, and the biographies I’ve personally created skew female.

Editors who align themselves with WiR tend to focus their editing primarily around the creation of womens’ biographies. Many of them are particularly interested in women who are also members of other groups they feel underrepresented, such as nonwhite or LGBT subjects. Because WiR is a quantity-focused project, they often create vast numbers of articles. Some subspecialize in bringing these articles to a decent quality (the WiR subproject “Women in Green”, which takes articles through the “Good Article” peer-review process); many simply create them in a good-enough-not-to-be-deleted state and move on down the list.

WiR is widely popular, but not faultless. I could catalogue a couple complaints — recency bias and a tendency to hagiography. One complaint you see particularly often is the BLP problem.

In 2005, someone made a Wikipedia article for the journalist John Seigenthaler. We don’t know who, and perhaps we never will. We know a surprising amount about them nonetheless; they didn’t make an account, and unregistered editors are represented by their IP address, so we know they lived in Nashville and that their internet was through BellSouth. The article was, in full with typos preserved:

John Seigenthaler was the assistant to Attorney General Robert Kennedy in the ealry 1960's. For a brief time, he was thought to have been directly involved in the Kennedy assasinations of both John, and his brother, Bobby. Nothing was ever proven.

John Seigenthaler moved to the Soviet Union in 1971, and returned to the United States in 1984.

He started one of the country's largest public relations firm shortly thereafter.

September that year, Seigenthaler discovered he had an article. He was not happy.

Given that Seigenthaler did not in fact kill Kennedy, nor was he ever suspected of it, the biography was libel. Fortunately, he didn’t try to sue anyone — but he could have. His friends replaced the biography with a less inaccurate one, and Seigenthaler contacted Jimmy Wales, the man who represents himself as the founder of Wikipedia, to ask he “revdel” (hide from public view) the offending revisions.

The sequelae of the “Seigenthaler incident” created strict policy standards around Biographies of Living Persons. Such articles must be meticulously sourced; they must be exactingly neutral in tone; they must hold themselves to the highest standards of encyclopedism. Opinions vary on how strictly to interpret BLP, and what different interpretations imply philosophically.

One thread you see, running through stricter BLP interpretations in particular, is the idea a Wikipedia article about you is a bad thing. This is quite clearly not what the vast majority of people believe, something you can tell from how obsessively people try to get them. Nonetheless…

“An article about yourself is nothing to be proud of. The neutral point of view (NPOV) policy will ensure that both the good and the bad about you will be told, that whitewashing is not allowed, and that the conflict of interest (COI) guideline limits your ability to edit out any negative material from an article about yourself. There are serious consequences of ignoring these, and the "Law of Unintended Consequences" works on Wikipedia. If your faults are minor and relatively innocent, then you have little to fear, but coveting "your" own article isn't something to seek, because it won't be your "own" at all. Once it's in Wikipedia, it is viewed by the world and cannot be recalled.”

-"An article about yourself isn't necessarily a good thing", a popular essay on the perils of demanding an article

“I don’t care what they say, as long as they talk about me.”

-Tallulah Bankhead (“this article needs additional citations for verification”)

The world tilts on two axises. One is that the most important thing possible is that everyone cares about you. The other is that the most important thing possible is that everyone cares about you. These are sometimes at odds.

Everyone wants a Wikipedia article. It’s the cultural sign you’ve Made It. Editors say that articles are pains for their subjects, that we have a high duty of care to them, that we could cause unbridled grief if we made them too hastily — then write articles for every Wikipedian who gets a couple local interest pieces. Revealed preferences, baby.

Nonetheless, la eseo is correct. The trouble with having an article about you is that it is made of all the things you’ve done. In this case, one of the things one of the subjects had done was extortion (the X makes it sound cooler). Reliable news sources covered her extortion scandal; so did her Wikipedia article. If you happen to not want “[name] extortion scandal” at the top of your search results, step 1 is not extorting people, but if you’ve failed that one, it’s easier if you don’t have a Wikipedia article.

An article will almost always be the top search result for someone’s name, above personal websites and public social media. This means whatever the article says is the most influential information about them there is. Sophie Jamal was once one of Canada’s most promising biomedical scientists, but now the first thing you see when you look her up, for the rest of her life, is “was at the centre of a scientific misconduct case […] received a lifetime ban from receiving funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and was named directly in their disclosure report, becoming the first person mentioned by name by the institute for scientific misconduct”. Now, if you happen to do something that the investigative team considers the worst case of research fraud it’s ever dealt with, people probably should know that about you. But I can’t imagine it’s the article she saw in her mind’s eye.

There are further considerations. Articles fall out of date. If the subject is a living person, this invalidates the whole article. People read articles because they want to know details of the person’s life, and will object if the article cuts out ten years ago. If the person hasn’t actually done anything noteworthy in the past decade — very often the case — it can’t be updated, meaning a problematic irrelevant snapshot is glued to the top of someone’s search engine results. Articles produce maintenance burdens, and those with few views can have serious issues for a long time; I’ve removed blatant trolling that lasted months. Articles can be inaccurate because of issues with the sources, which can have real implications for peoples’ lives and careers. Surreptitious manipulation of articles, such as somebody subtly downplaying their competitors in a field, can seriously undermine the whole project and evade detection for a long time.

So, obviously, it’s a great and fantastic thing with no downsides that the largest bloc of content creation since 2015 is focused on making more biographies.

Fundamentally, Wikipedia doesn’t want more biographies. They are, as you may have gathered, a pain in the ass. They are almost uniquely vulnerable to swinging deliriously between advertorial and libel. Nonetheless, we see ever-increasing numbers of them in the name of overcoming systemic bias.

Some editors explicitly define their purpose on Wikipedia as biographers, in the aim of defeating such bias. They write many short articles in subject areas where notability is straightforward to demonstrate, such as sports or academia or the visual arts. The most archetypal version is “women in science”, out of the idea that since STEM fields are some of the extremely few upper-middle-class occupations that skew male even in young cohorts, it is particularly important to present women in such fields as role models.

We’ve discussed before the perils of STEM obsession, but it is what it is. One is reminded of that Roald Dahl rewrite where the warning that a witch could be posing as “a cashier in a supermarket” was replaced with one that she could be “working as a top scientist”. This is a spectacular misinterpretation of the intent, and a demonstration of how useless adults become when they forget their childhoods. Children (modulo self-checkouts) encounter cashiers in everyday life; the point is a warning that horror lurks behind the mundane, a way to set alight a child’s hypertrophic imagination with the terror that the kindly woman at the shops could be something else entirely. Very few children interact regularly with scientists.

Similarly, the drive to represent respectability overcomes no bias at all. Wikipedia has long been troubled by a dissociative drive for respectability. Fiction is a particular area of dispute, one where no matter how much fiction-related content is marginalized it never seems to be enough. We have, as you might expect, exceptionally good coverage of subjects people tend to develop interests in the details of — trains, roads, ‘nerdy/stats-based’ sports such as cricket/baseball/esports, military history. Also hurricanes, for some reason. Some of these subjects are considered more ‘respectable’ than others, and many people rend their hair at how frequently they show up compared to ‘worthy’ matters. I’ve never found improvement to be a zero-sum game. A definition of ‘systemic bias’ that nonetheless considers respectability a useful concept is also useless; any group that actually is marginalized is so because it doesn’t play those games. If you base people on their manners, you select for the children of manners classes.

More concerning is the turn to hagiography. Most articles made out of the drive for respectability are on deeply inoffensive figures. I mentioned Jamal before, a “woman in science” whose article I created. Though she was notable for years before I got around to it and included in a highly-viewed list of people involved in scientific misconduct, no one had thought to turn that redlink blue. It would doubtlessly improve Wikipedia’s coverage of women in science — including how science can be misinterpreted and misrepresented, how terrifyingly common this is in many fields, and how people seen as respectable authorities are not immune. But this redlink sat for years through the creation of many articles on researchers. You have to wonder how many have skeletons in their closets while we present them so straightforwardly.

We land back at extortion.

The intent of the creator was clear. “Women of colour in politics — great, we’re countering systemic bias!” The same writer has created hundreds of similar articles. They certainly had no intent to defame, no idea at all of the controversy — possibly had never heard of the individuals before seeing their names on a list of redlinks. The subjects looked at this shared creator and decided it was someone out to get them. What does it imply about you, if you think the only reason someone would make those articles is if they were out to get you?

This is not the first time I’ve seen a subject decide their WiR article was an attack. I was once reading back through old conversations on the Wikipedia Discord server and saw an editor distressed — he had written an article on a woman of colour involved in a media diversity initiative, and been alerted she was angry on Twitter about the article she hadn’t “authorized” and wanted to “take it down or take ownership”. The comments talked about how dumb it was they had “crossed her”, and commiserated about their own experiences having an article that people kept reverting them when they edited. One respondent seemed aware that WiR existed — describing it as “using your likeness to salve their guilt”, grimace-emoji and all.

The subject headed to the talk page of the article, a flattering biography of her various industry accolades, and demanded in all-caps it be rewritten to sound even more like a LinkedIn profile. She was declined. The article still exists, now in multiple languages, and remains honeyed in tone by all standards but hers.

There is a conundrum here. The drive to represent as many people from X demographics as possible conflicts with the drive to maintain biographies in a high-quality state. It also interacts complexly with the desires of article subjects themselves. It’s reasonably (though not universally) agreed that Wikipedians have a duty of care to article subjects, at least in the “let’s try not to get sued for libel” sense. It is not clear how to prevent traducement and hagiography all at once. It is probably not possible; many subjects will look at a paean to their works and decide it’s someone out to get them. Many non-subjects will look at an article on their rapist and try over and over again to add their Medium article talking about the rapes, getting reverted every time, because Wikipedia cannot source rape accusations to a blog post and not get fucking sued. But there goes the truth, infected by shadows.

There are many areas where Wikipedia’s coverage is terrible. Lately I’ve been writing about books. Books have a low notability threshold, they’re easy to write articles for, easy to bring to a point sufficient for our quality-assessment peer review processes, and fun to read. Somehow, we have no articles on them. Other people look at other gaps, like the visual arts or religious studies or history or anything to happen in a non-Anglophone country, Jesus Christ. Most of those things don’t try to dox you.

It is difficult to talk at much length about WiR, because no one wants to give the impression of sexism. But the problem is the problem of biography; a very similar post could be written (and should be written) about sports biographies, most of which are of men. The irony is that articles written with such intentions are misinterpreted in such ways. The issue is a microcosm of Wikipedia’s issues handling biographies, the problems that happen when you have 5000 people maintaining six million articles, of which two million are bios. When you use someone’s likeness to salve your guilt, sometimes their guilt comes out, too.

Great write up, I learned some new things!