The past decade has seen a Vibe Shift in autism research. While quantitative studies of childhood autism still dominate the picture, there is an increasing recognition that, at some point, children become adults. This is not always continuous; the obsession with particular kinds of underdiagnosis means a lot of research on autistic adults is on adults who sought out diagnosis, a decidedly unrepresentative group of autistic people. Still, if it’s that or samples with a 75% intellectual disability rate, I might have to pick the “masking” types.

Some funny things fall out when you study adults that you can’t see yet in children. The perpetually funniest is that the 2008 “[bong hit] uh, dude, what if autism and schizophrenia are like…opposites?” idea immediately collapses any time you study adults, who keep inconveniently having both:

(for reference, the odds ratio for people with a schizophrenic first-degree relative is around 81)

But this is far from the strangest thing that comes out in the wash. Croen et al. (2015) is studying a large sample of autistic adults, but a young one. The average age is 29. 85% of participants are under 50, and 98% are under 60. You’d expect very little burden from aging-related disease in this sample, and indeed you see that, after allowing for generally poorer health. Except for one little aside.

Hey, how the hell does a cohort with an average age of 29 have enough Parkinson’s for it to show up?

I first found the autism–Parkinson's mystery in Starkstein et al. (2015). Tracing my life at the time, I must’ve read it c. 2017–2018. I was at my dad’s house, looking through the study with an increasingly raised eyebrow. He looked over, asked me what I was up to.

“Reading research on autistic adults,” I said.

“Oh, cool. What’ve you found?”

“They all have Parkinson’s.”

Starkstein et al. (2015) is a writeup of two studies, capturing different people across different continents — with one in North Carolina and the other in Perth, it’s the most genuinely confusing use of the “WA” geo-acronym I’ve seen in some time. It’s one of few studies on autistic people, even fewer in 2015, that focuses on middle-aged and older autistic adults. The cohort is what you might call “low-functioning”, if you don’t have a disgust response to the term. Most people involved test as having severe intellectual disabilities (the largest IQ subgroup in either cohort is <35). A vast number of them take neuroleptics/antipsychotics, drugs that amongst other things give you severe and potentially irreversible parkinsonisms.

Around a third of them had significant parkinsonisms, many severe enough for a full-blown diagnosis. It’s possible to notice “neuroleptics” here, blink, and file the study away. There’s just one small problem with doing that:

Is the sample size small? Yes. Is 20% completely, absolutely insane? Yes!

Parkinson’s generally onsets in one’s 60s or later. The error bars on this are bigger than you might think — some meaningful minority of people with Parkinson’s develop it in midlife or earlier — but it’s distinctly a disease of the elderly, on the population level. Around 1% of people in their 60s have Parkinson’s, increasing slightly from there (DeMaagd & Philip, 2015; Wickremaratchi et al., 2009). How the hell can 20% of people in their 50s have Parkinson’s unless something weird is going on?

To be clear, there are many weird things that can go on — most prominently, it’s plausible most of those twenty people were on neuroleptics at some point, and not totally out of the sphere of plausibility that they stopped them due to complications. There are way too many factors here to draw conclusions, but the number is so striking to be a starting point for research.

“Starting point for research”? Ha ha ha, no one cares about autistic adults, good luck. “I thought you said they do now?” Yeah, but not, you know…the autism part. Most research on autistic adults relates either to the implications of adult autism diagnosis — an important topic, but one with a complicated relationship to either autistic people diagnosed early in life or never-diagnosed autism — or to autism as a broad proxy for maladaptation, a general Everything Is Wrong marker, which is often incompatible with the experience of more specifically autistic people. A particular issue is that definitionally, research tends to be based on adults who self-identify as autistic, who tend not to be particularly representative of either all autistic adults or of diagnosed ones. This makes it difficult to pick out signals, like Parkinson’s, and determine their potential cause. If “autism” is assumed to be an omni-risk for all possible issues, including ones where their actual correlation with autism is deeply questionable,2 real issues can’t be spotted. You have to go deeper. What are autistic children like?

Motor symptoms are an underrecognized part of autism, despite being far more important than generalized “social impairment”. Stimming/repetitive behaviour tends to be the most visible element of this, but characterizations of autistic children as “clumsy” trace back a long way. Nayante et al. (2005) go as far as to suggest that autism is a movement disorder. Autistic people have strange gaits and may-or-may-not (autism brain research still sucks) have alterations in brain areas controlling movement. Rats with cerebellar lesions supposedly have “autistic-like behaviours”, though you should not trust psychiatric animal models as far as you can throw them. More recent research suggests the autism/weird gait association is “real”, occurs across a broad spectrum of ASDs, and probably at least somewhat cerebellar and frontostriatal.3

“Is that weird gait like a Parkinson’s gait?” Wait, you thought we could narrow it down further than “it’s weird”? Look, man, we barely know how to narrow down autism. But both the cerebellum and the frontostriatal region are affected in Parkinson’s, so…maybe?

What are people with Parkinson’s like?

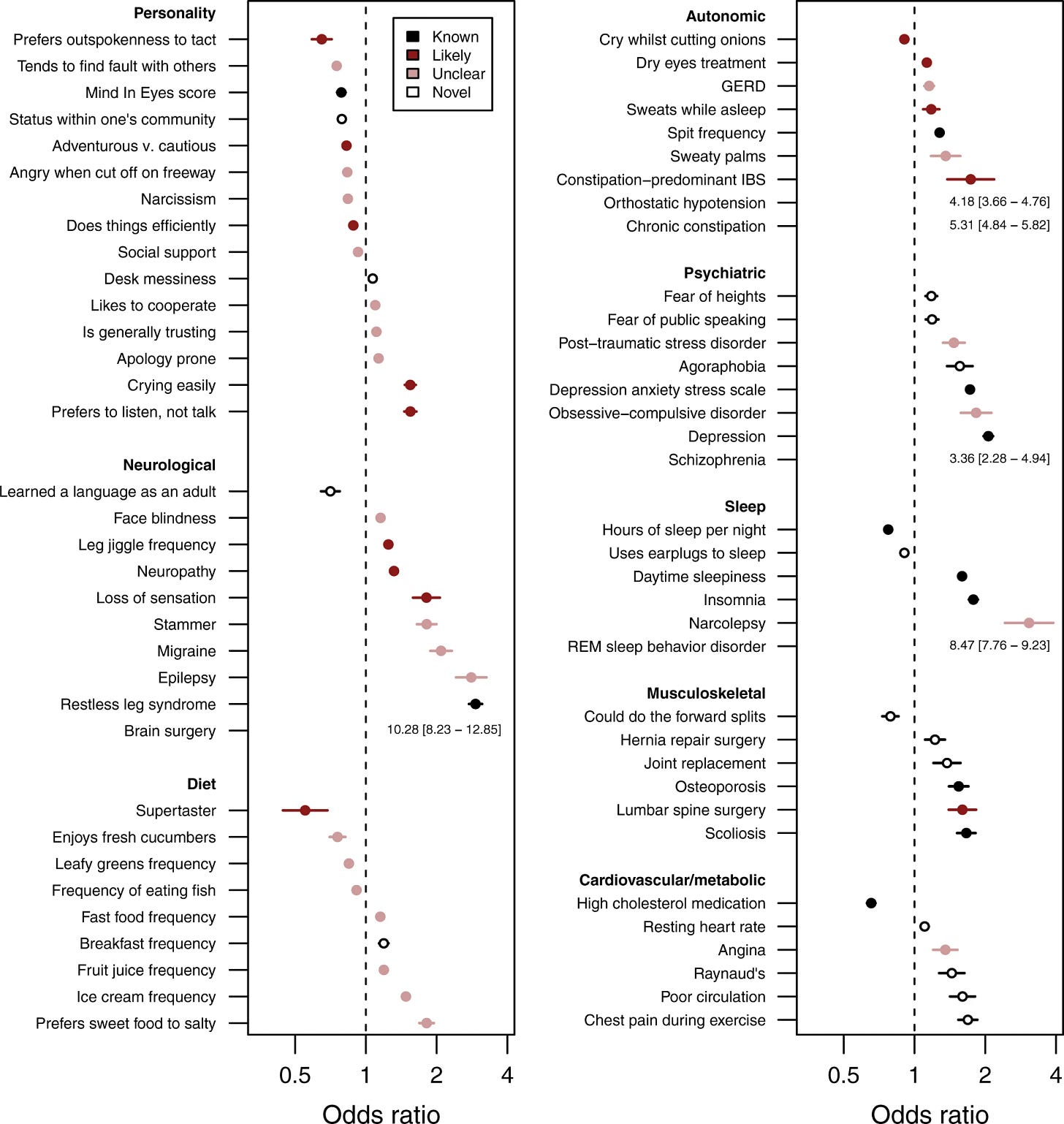

Heilbron et al. (2019) looked at an array of potential Parkinson’s correlates. Based on several thousand cases and over a million controls, they dutifully built a coherent profile of “Parkinson’s-linked personality traits” — all of which are anticorrelated with autism.

Now, autistic people have fairly poor Mind in Eyes scores, which is an interesting hit there. But “preferring tact to outspokenness”,4 “generally trusting others”, “being apology-prone”, and “preferring to listen rather than talk in conversations” are not traits I would traditionally associate with autistic people.

Of course, it’s not like schizospec people are particularly tactful or trusting either, and there’s still a 3.36 OR for Parkinson’s in schizophrenia (astute readers will notice this is lower than 32.73). Schizophrenia has a blatant confounder — most people diagnosed with SZ take neuroleptics,5 which are antidopaminergic and cause parkinsonisms. Because people are obsessed with spurious “opposites”, this comes as a surprise to some researchers, who naively assume “high dopamine??? low dopamine???” and fail to account for decades-long antidopaminergic exposure.6 Is autism–Parkinson’s just a spurious risk of this kind, where the whole thing is mediated by the horrifying proportion of autistic children who take these drugs from early life?

Well, maybe. It’s certainly a factor. But let’s pause — did you just overlook “spurious risk of this kind”?

When people talk about schizophrenia, they tend to focus on “positive symptoms” — delusions and hallucinations. This is less than half the story. Positive symptoms are the interesting part, the shamanic sickness, the part you spin narratives out of when you see them in the rear view mirror, the part people recover from and become weller than well. The part that sucks, the part that causes long-term disability, the part that makes it hard to actualize your Greater Wellness, the part that predicts prognosis a thousand times better, are “negative symptoms”. The distinction between positive and negative symptoms is not a solid wall, but in the real world, you can classify them well enough. Archetypal negative symptoms include anhedonia, a lack of motivation, difficulty thinking or expressing your thoughts, restricted affect (few or no facial expressions, monotone speech, etc), and social isolation.

It is…not easy…to construct a narrative of “how negative symptoms emerge” that both fits clearly in a simple dopaminergic model, and matches how negative symptoms actually emerge.7 Negative symptoms are also interestingly nonspecific. They can look a lot like, well, autism. They can look a lot like (and often are) depression. They can look a lot like (and often are) sleep apnea.8 And they are, as it happens, commonly seen in Parkinson’s.

Is there a “real” SZ-Parkinson’s link, just way smaller than the extreme confounder of chronic neuroleptic exposure? It’d be interesting to study primarily-negative schizophrenia and see if, controlling for neuroleptic exposure, it comes with a higher Parkinson’s risk. You’d have a huge pain getting a good sample — primarily-negative schizophrenia tends to start younger and involve higher drug doses being thrown at people, especially given neuroleptics both cause and worsen negative symptoms — but it’s a great thing to put in the Land of Theory.

But this still lands you back at “the wrong personality traits are associated”. Where do you go from there?

Let’s be clear — the odds ratios are pretty small, compared to the possible OR for autism itself. They could theoretically be true at the same time. It’s not…something you should brush away so easily, but it’s not impossible.

The study itself reports the finding as “people with PD tended to report being less quick to anger, less outspoken, and less talkative”. (“Less talkative” is fair.) They review a number of previous studies that found people with Parkinson’s were more introverted and neurotic, or more introverted and inhibited, or — funny, that — “introspective, over-controlled anhedonics” who live by inflexible rules. They express uncertainty as to whether the whole deal was premorbid or postmorbid — Parkinson’s causes apathy by way of dopamine depletion, which makes you less talkative, outspoken, and emotional. If the disease itself causes personality changes before the onset of motor symptoms (probable), it gets real tricky to real-world distinguish them.

Modern medicine is in love with hard-biological explanations. To declare a “psychological” or, heavens forbid, “psychosocial” explanation for something is to betray the afflicted. Everything has to be caused by biological factors alone, with any suggestion otherwise a sign you’re blaming the patient. Does this help anyone, ever, in the entire world? Does it avoid making things worse? Uh, let’s just ignore that.

This is an overcorrection, not a Law of History. For much of the twentieth century, it was the mind that ruled the brain, not the converse. You thus find yourself pouring through old papers that discuss the psychogenic causes of Parkinson’s — the degree to which the disease was caused by its patients’ uptight and rigid manners, spiralling in old age to the point their bodies themselves froze in place. If there is a middle ground between “all medically unexplained syndromes are physiological and all psychological distress is an idiopathic Chemical Imbalance” and “you give yourself Parkinson’s by having a stick up your ass”, we haven’t found it.

But where does that idea come from?

Todes & Lees (1985) — the “introspective, over-controlled anhedonics” paper — remarks on the “surprising degree of uniformity of opinion” regarding premorbid personality in Parkinson’s. Writers across nations and decades were unanimous that there was a Type of Guy who got Parkinson’s, and they had a solid idea who he was. It would be convenient for us if this guy was in any way autistic. Unfortunately…

The “Parkinsonian”, as described by Todes & Lees, is as allistic as rigid introverts get. “One would rarely find a Parkinsonian patient who would discard social norms” (p. 98). Patients were seemingly obsessed with “the idea that they should act according to social norms and not in response to their personal feelings”, with any drive for independence or freedom held back by existing “within a framework of social conformity” (p. 97). They were inflexible workaholics, yes — but marked by being “courteous, polite, honest, trustworthy, conscientious, punctual, and [having] a strong desire to assert themselves socially” (p. 98). There’s a lot to say about the near-pathological honesty of many autistic people, but I don’t tend to feel the demographic is renowned for politeness or social climbing.9

Combining this with Heilbron’s data, there’s really no way to salvage the “inherent link” hypothesis. Autism is not rare, and ‘autistic people’ shade into the general population; many undiagnosed or undiagnosable people are colloquially autistic. You’d expect studies like this to describe a “broad autism phenotype” of sorts if Parkinson’s was really that common in autism, not its exact opposite.

Of course, these traits are also untrue of schizospec people. That connection would be overwhelmingly neuroleptics-based. So we must land somewhere similar — astronomical rates of parkinsonisms in autism are neuroleptics-mediated, ĉu ne?

Geurts et al. (2022) is a study of parkinsonisms in older autistic adults from two countries, but in many ways, it’s the opposite of Starkstein et al. (2015). It’s much larger, with over 500 participants. All participants were “high-functioning” the way that term was defined when it was a diagnostic concept (had IQs above 70).10 But they weren’t just squeaking in under the wire; most had well above average IQs and, despite being in a demographic (people aged 50+) with below-genpop educational attainment, had attended or graduated from university. Most reported “Asperger’s syndrome” as their diagnosis. Most were in romantic relationships. The American sample had the suspicious 50-50 gender ratio you see in too many adult autism studies. Participants were on average diagnosed with autism in their late forties or early fifties; none of the Dutch participants were diagnosed before adulthood. Most importantly, “only” the insanely-high-proportion of 10% of participants took neuroleptics, a much smaller fraction than Starkstein’s sample.

I’m inherently suspicious of studies like this. The “milder” autisms are very underdiagnosed, and under perfect diagnosis we’d be detecting many adults, but people who acquire an adult autism diagnosis are often those who sought one out, who are not representative. “Accidental” diagnosis (e.g. people with autistic children), yes. People interested in therapy for its own sake…well, I’m pretty sure that anticorrelates. But I’m also inherently suspicious of “low-functioning” autism diagnosis, which often seems like a game of finding the most insane dual diagnosis possible (all-time winner: Williams syndrome), so it should balance out.

What did Geurts find?

…oh.

So the good news is, this is definitely not one of those misdiagnosed samples! The bad news is, they still all have Parkinson’s. In fact, the numbers are eerily close to Starkstein’s completely different sample.11

While many fewer people in this study took neuroleptics than in Starkstein, or in most studies of prescription rates in autism, it’s still well above the general population rate (somewhere in the neighbourhood of 1.5%). How did this interact with parkinsonisms? According to the researchers, “not at all”! Their numbers are overwhelmingly in favour of the null hypothesis.

None of the Facts about the World fit each other. Autistic people are very likely to have clinically relevant parkinsonisms, but neither Parkinson’s nor autism are rare, and all the data we have on the “Parkinson’s personality phenotype” is totally incompatible with autism. Many autistic people take notoriously parkinsonsgenic drugs, but this keeps coming up as a null factor. These cannot coexist.

And yet.

How do we square this circle?

One possibility is that autistic-parkinsonisms are not Parkinson’s per se. This ties back in with the question of Parkinson’s-like motor symptoms in autistic children. For one, how often are these “parkinsonisms” lifelong?

Geurts reports that a significant minority of people who answered yes to any given screening question reported it as lifelong, or at least beginning before adulthood. The questionnaire can be found here (bolded questions); I’m in my twenties and have nothing that could be sanely called a parkinsonism, and would answer yes to at least one. Autistic people are also great at interpreting questions in all sorts of interesting ways, and the two with the highest hit rate (“Have you ever noticed stiffness in your legs?” and “Have you become slower in your usual daily activities?”) sound like they were…probably not being answered the way an allistic person taking a Parkinson’s screener would answer. (“Ever? That’s a big question! Well, better think about all the times my legs felt stiff. If I recall correctly, once was the 16th of June, 1994…”)

This isn’t solely explanatory, though (except for “slowness” being a description of normal aging, which looks suspicious). The mean age of onset for every response is well into adulthood, so there’s clearly a component of an acquired skill being lost or getting worse.

Does this regression/degeneration cluster with everything you’d expect Parkinson’s to cluster with? Maybe not. Geurts included the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire — basically a test of absent-mindedness — amongst the screeners. While the questions can be expected to have some ceiling effect for autistic people (sample question: “Do you say something and realize afterwards that it might be taken as insulting?”), the team hypothesised that people who screened positive for parkinsonisms would have higher CFQ scores, as well as more physical and mental health concerns. Turned out, they didn’t.

This is a strange finding. Parkinson’s proper is associated with all sorts of physical and mental health problems, as you might assume. It’s also associated with dementia. At diagnosis, around a third of people with Parkinson’s have some level of cognitive dysfunction; ~50% develop full-blown dementia by 15 years post-diagnosis, and ~80% by 20 years (Hanagasi et al., 2017). The CFQ is probably not the best tool to assess potential dementia prodromes in autistic people, but in the Dutch half of the sample, it was anticorrelated with parkinsonisms — people who screened negative had higher CFQ scores, on average. Whatever it’s picking up on, it’s definitely not picking up on early-stage Parkinson’s cognitive dysfunction.

As the researchers note, this suggests that whatever causes autistic parkinsonisms — or, more accurately, “autistic high scores on this particular screening questionnaire” — is something other than classical Parkinson’s disease. This can also explain a lack of association with neuroleptics. Neuroleptics cause tremors and dyskinesias, which make up a fairly small proportion of all reported parkinsonisms here, and an often-lifelong one when they did exist. Whatever causes “parkinsonisms” in autistic aging is…something else.

But that’s Geurts, not Starkstein. The former study asked a few hundred people to self-report answers to a short screener. The latter went out there in the field, with clinicians assessing full-blown Parkinson’s based on gold-standard diagnostic tests. Whatever this Parkinson’s-looking thing is, it’s something that looks exactly the same to “a neuropsychiatrist with extensive experience in rating parkinsonism in complex patients, such as older adults with psychosis, dementia, or severe depression” (Starkstein et al., 2015, p. 3).

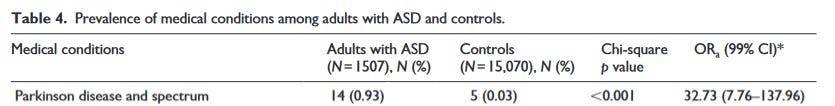

And it’s diagnosis that’s elevated, not just symptoms. Let’s circle back to Croen et al. (2015), the first study we looked at. This is a study of 1507 adults who were enrolled in a particular American health care provider (Kaiser Permanente Northern California) between 2008 and 2012, who were diagnosed with any ICD-9 autism spectrum disorder.12 About three-quarters were covered by the insurer proper, and one-quarter by Medicaid, the US’s government health insurance for very low-income people. Participants had a mean age of 29, and a median in their early twenties (52.4% were aged 18-24). About 20% were diagnosed with an intellectual disability, which seems fairly representative of large diagnosed populations. They were compared to 15,070 controls matched for age and sex (~75% male), but demographically different in other respects (less white, less Medicaid-y).

Again, nearly 1% of the autistic participants were diagnosed with Parkinson’s…

…compared to 0.03% of controls. Which is the number you’d expect in a young adult cohort! Even with ten times as many controls as autistic participants, more autistic participants (14 of 1507) were diagnosed with Parkinson’s than controls (5 of 15,070).

This isn’t seen for other nearly-always-late-onset conditions. Of the aging disorders that had high odds ratios in the autistic participants, most looked like early-onset forms correlated with autism diagnosis (e.g. more autistic people than controls had hearing or vision problems). Osteoarthritis was equally rare in both groups (OR 1.06, 99% 0.68-1.65). Cancer was nonsignificantly rarer (OR 0.66, 99% 0.39-1.14), an odd finding I’ve seen before.13 “Lifestyle disorders” (e.g. hypertension, diabetes) were somewhat more common in autistic people, who are not known for their perfect diets and love of exercise, but the ORs were a lot lower than Parkinson’s.

Croen isn’t the only study like this. Hand et al. (2020) studied autistic people aged 65 and over who were enrolled in Medicare, the US’s government health insurance for the elderly (not to be confused with other countries’ things called Medicare).14 This is, notably, an older cutoff than any of our other studies — and the only one in the range where Parkinson’s becomes detectably common in the general population. With 4685 autistic participants and 46,850 controls, it’s the largest one we’ve looked at. Most were in their late 60s, but they had a full spread of ages (4.5% were 85 or older). Just over 40% were diagnosed with an intellectual disability.

You should expect some differences between Hand and Croen. For instance, schizophrenia diagnosis is more common in young adults, so this older group should have a lower —

— ah.

(Seriously, 17.8%? A lot of that would be questionable diagnosis — diagnostic substitution to schizophrenia is a known problem for older autistic people — but seriously?)

But you’d expect more Parkinson’s in both groups than in Croen, and this is what you see:

6.1 is a lower odds ratio than 32.73, which at least is encouraging in an “it comes back down to earth in higher-age-risk samples” sense. But it’s an insane OR — the only higher one for physical illness is epilepsy, which has a notorious strong association with autism. It’s higher than the OR for gastrointestinal issues, which everyone is obsessed with. It’s higher than that for mood or sleep disorders, and on par with anxiety.

Neither Croen nor Hand discuss rates of neuroleptic prescription, but they can be assumed to be high. Starkstein’s rates are very high — 37% of the American sample, 78% of the Australian sample — which is, unfortunately, not too far off the autistic average. Because autism in and of itself is strongly associated with neuroleptic prescription, and because so many people in both Croen and Hand were dual diagnosed with other things so associated, one can assume rates at least comparable to the “inconsistent, but consistently absurd” rates reported in most studies.

Parkinsonisms were slightly-more common in people in Starkstein’s studies who took neuroleptics (31% vs 20%), but the differences lacked statistical significance, and also, both are insanely high. But a consistent trait to both Starkstein and Geurts is that while they reported current neuroleptic use, they had no data on lifetime use. Geurts only had a snapshot of people at participation. Starkstein found that the people not taking neuroleptics who were diagnosed with Parkinson’s hadn’t taken them in the past five years, but they couldn’t be sure about longer, and the lifetime rates of neuroleptic use for people who are diagnosed with an intellectual disability or live in institutional settings are…not low!

Neuroleptic-induced movement disorders are routinely irreversible. Classical tardive dyskinesia (involuntary facial, truncal, and limb movements) persists in 95-98% of cases following drug withdrawal, unless you catch it very early. Parkinsonisms without TD are more likely to resolve, but persist in the intriguingly-broad-range of “10-50% of patients” (Shin & Chung, 2012, p. 19). At least some people develop a relapsing-remitting pattern. The distinction between different kinds of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders doesn’t seem to be “real” — if you have one, you’re more likely to have others, and people tend to underreport them as side effects, so given prevalence estimates can be thought of as low counts.

Intellectually disabled people are more vulnerable to neuroleptic-induced movement disorders. It’s likely this finding is also true of autistic people, because “vulnerability”-type findings often are, and because diagnosis of ID in autism is much messier than presence of ID in autism. They’re also more common in women, while idiopathic Parkinson’s is slightly more common in men. Autistic parkinsonisms seem more common in women; more women than men in Geurts’ American sample screened positive, while in Hand’s study, women had an 8.2 OR for Parkinson’s compared to 5.4 in men. This tracks to something at least exaggerated or unmasked by neuroleptics.

Here’s a fun one: autistic people are less likely to smoke. Does that have anything to do with it?

You should be ultra-skeptical of any “benefits of smoking” study, which tend to be funded by cartoonishly evil Big Tobacco execs, rubbing their hands and laughing while torturing a child to death. But all the ultra-skepticism in the world still has to raise an eyebrow at the inverse association between smoking and Parkinson’s. The evidence is overwhelming, stronger amongst current than former smokers, holds for multiple kinds of tobacco use, has been repeatedly found for decades and over some of the longest longitudal studies anyone’s ever done, and resists easily-checked confounders (Allam et al., 2004; Gallo et al., 2019; Li et al., 2015).

Rates of tobacco use seem pretty low in autistic people, though the nature of this lowness is unclear. They might be lower than you’d expect in the general population, or just lower than you’d expect for things like the mental illness rate in autism. Some studies report counterintutively high rates, but this seems to be routed through confounders — people diagnosed with ADHD have astronomical smoking rates, and ASD/ADHD is a common dual diagnosis. At the very least, autistic people who aren’t diagnosed with anything with the inverse association have low tobacco use rates.

As mentioned earlier, around 1.5% of the “community-dwelling” (i.e. not institutionalized) population in the United States take neuroleptics. This population is much more likely to smoke than genpop — 38% of people in the NHANES sample who take neuroleptics are current smokers, compared to 18% of controls. Some reader is half-remembering a stat that schizophrenic people smoke like chimneys, and assuming this is just picking up on that. But less than 10% of people taking neuroleptics are diagnosed with schizophrenia!

If literally all schizophrenic people smoked, and the remainder smoked at genpop rates, you’d get around 28% smokers. The real smoking rate in SZ is much lower, globally around 60%, and lower in the West (smoking rates are super-high in the East). Assuming a current-smoker rate of about 50% for SZ in the United States, which is probably in the ballpark, you need around 30% of the rest to be smokers.

Do neuroleptics cause smoking? They make you anhedonic and unmotivated, which people report smoking to avoid. Desire to smoke is positively associated with neuroleptic dose (Barr et al., 2008). Practically no studies look at smoking and neuroleptic use in populations without a schizophrenia diagnosis, and because schizophrenia is an Outgroup Label, research on people given it tends to have the same “so, obviously, these people do this because they’re weird and incomprehensible” you see in some strains of autism research. These numbers are suspiciously high, though, in ways that suggest a causal smoking-neuroleptics relationship. I mean, there’s definitely a causal obesity-neuroleptics relationship, and the odds ratio for obesity here amongst people taking neuroleptics is “only” 1.54. The odds ratio for smoking is 3.14!

So neuroleptics cause parkinsonisms, and smoking is inversely correlated with Parkinson’s. Is it also inversely correlated with neuroleptic-induced parkinsonisms? Seems like it is, though it’s messy and uncertain. If we have a population with low smoking rates and high neuroleptic prescription rates, is that a population at uniquely high risk for parkinsonisms?

It seems probable that it is, and this would apply even to autistic people who never took neuroleptics, because the effect remains true for idiopathic Parkinson’s. This is assuming the relationship is causal, which it may or may not be — depending how you read the “Parkinson’s personality” thing, it could easily be “the risk of Parkinson’s is increased by having this personality somehow, which is anticorrelated with smoking”. But if smoking has any preventative effect on neuroleptic-induced movement disorders, that implies at least some causal role.

Still, does that get you to 20%?

There are many autisms. People tend to think of this as, if you will, “north/south” rather than “east/west”. Autisms are distinguished based on “severity”, because people can’t — or don’t want to — see what they have in common with a “severely disabled” person. In reality, these distinctions disintegrate when you hold them up to the light. What instead appears is the way autism interacts with a person’s person, with everything they are and everything they do.

This is most prominent in the overlap between autism and many personality disorders. Some personality disorders, in retrospect, were clearly written in part as descriptions of autism long before anyone considered it as an adult diagnosis.15 Some are commonly diagnosed in autistic people, but also in allistic people. No single personality disorder clearly describes all autistic people, but many describe a lot more autistic people than they do allistic people.

One PD that describes some autistic people is “obsessive-compulsive personality disorder”. OCPD…ers are rigid, detail-oriented types who hard prioritize things over people. This is a reasonable enough description of autism, but the devil is in the details. Many OCPD types are obsessed with a particular “virtue of conscientiousness”, where hard work for its own sake is the highest good and any sort of leisure inherently suspicious. They are “rigidly deferential to authority and rules”; their laws are often external, unlike the classically autistic profile of “inventing standards from first principles”. They make decisions by “rules and established procedures”, becoming adrift when left to their own devices. They are, in short, cops.

This overlaps with both an autistic profile and with the proposed “Parkinsonian” personality. Is Parkinson’s risk primarily in the “OCPD-autism” cluster?

Nicoletti et al. (2013) found a strikingly high prevalence of OCPD in Parkinson’s — 40% of participants! Personality disorder prevalence is the worst thing in the world, and every estimate disagrees with every other estimate, but 40% is decidedly out of general population range — even considering that OCPD tends to come up as the most or near-most common PD. Participants were quite young (average age 59), and 12% had onset before age 40, which is probably around twice average. This suggests a pretty high OCPD prevalence in earlier-onset forms of Parkinson’s.

Later, the same researchers looked at a sample of people with recent-onset Parkinson’s who hadn’t yet taken disease-modifying drugs, to check that it wasn’t a consequence of the diease itself. They found another extremely high rate (37.5%). Importantly, a high rate of depressive PD they found in the previous study wasn’t replicated here, suggesting that a “real” disease-related effect (Parkinson’s making people more depressive) was identifiable — and, by extension, that the OCPD thing is probably “real”.

One problem is that the OCPD rates they found in controls were insanely high (10% and 17.7%, respectively). OCPD is pretty common, but…not that common. It’s high enough to be suspicious that they had a very lax OCPD definition. It’s at least directionally right, though.

Later, the same team again (Luca et al., 2022 — Nicoletti was the corresponding author this time) looked at REM sleep behaviour disorder. RBD, where you start acting out your dreams in your sleep, is a common prelude to Parkinson’s. This study was smaller than their previous ones, but the pattern was the same. 55.2%(!) of participants with RBD had OCPD, as did 46.7% of those with Parkinson’s and…13.3% of controls. Yes, OCPD is common, but this is about twice the high-end genpop estimate. Three different studies across a decade, you have to take the “they’re quick to diagnose OCPD” hypothesis.

But they’re clearly not 40% quick. Whatever the real number is, it has to be high.

Autism and “autistic traits” are common in OCPD (Anckarsäter et al., 2006; Gadelkarim et al., 2019; Hofvander et al., 2009). Given the high genpop prevalence of OCPD, OCPD-autism is probably one of the more common autisms. Could this explain some of the Parkinson’s rate? If OCPD-autistic people are a uniquely high-risk group, you can square the circle of why the Parkinson’s personality phenotype is “wrong”. Most people somewhere in this personality cluster will be allistic, and have allistic presentations like “being ultra-concerned with their social position” or “prioritizing tactfulness in conversations”, but more will be autistic than usual. Throw in neuroleptic exposure…

(Some readers will be thinking “but what about severely disabled people?”. Severely disabled people are people. They have personalities. They vary on personality dimensions. It’s harder to test them, but I bet a lot of relatives and care workers would have interesting clinical impressions if you asked.)

Still, does that get you to 20%? The problem is just how high the rate is. You need multiple factors, and none of them suffice.

Let’s recap:

Both full-blown Parkinson’s disease and clinically relevant parkinsonisms are more common in autistic people than the general population. They start at younger ages than Parkinson’s usually does.

Maybe 6-7% of elderly autistic people have a clinical Parkinson’s diagnosis. Maybe 20-30% of autistic people in their 50s and older have parkinsonisms of some description.

This is true across diverse samples in multiple countries, all across the spectrum.

There’s a distinctive and well-reported “Parkinsonian personality”, but it doesn’t look like autism.

It overlaps a lot with “obsessive-compulsive personality disorder”, though, and that also overlaps with autism.

Autistic children have weird motor patterns that are maybe sometimes like those in Parkinson’s, if you squint.

Some autistic “parkinsonisms” are probably lifelong.

An extremely large share of autistic people take parkinsonsgenic drugs, or have taken them in the past. Present use of parkinsonsgenic drugs is not associated with current parkinsonisms, according to the only studies that have looked at it. No one has looked at past use.

Smoking rates might be relatively low in autistic people, but data here is surprisingly tricky, and it’s not clear what the “relatively” benchmark should be. There is a strong, possibly causal negative association between smoking and Parkinson’s. There is more likely than not to be a negative association between smoking and drug-induced parkinsonisms.

For a relatively broad definition of “parkinsonisms”, autistic parkinsonisms don’t correlate with things they “should” correlate with, like health and cognitive issues. We don’t know about narrower definitions.

There is just enough here to raise many more questions than it solves. Here, have some questions:

Do autism and Parkinson’s run in the same families?

Do autism and early-onset Parkinson’s run in the same families?

Do autistic smokers have fewer parkinsonisms?

Does past use of neuroleptics correlate with parkinsonisms or full diagnosis?

Seriously, does present use? The largest study showing no present-use association had relatively little neuroleptic use, and a broad definition of parkinsonisms.

Do people who fit criteria for both OCPD and autism have more parkinsonisms? Are they more likely to have Parkinson’s proper?

Do young autistic people have more parkinsonisms-broadly-construed? Is this just an autism motor symptom?

Some schizospec people have a lot of OCD tendencies, or fit many OCPD criteria. Do these people get more parkinsonisms?

Do people on both the schizotypal and autistic spectra get more or fewer parkinsonisms, controlling for neuroleptic exposure?

How many people with Parkinson’s are eligible for an autism diagnosis?

How many people are eligible for an autism diagnosis? We might, uh, want to sort that one out first.

There’s clearly something big here. But we don’t know what it is, because adult autism research sucks. Awareness of autism is recent enough that we’re only just entering the age of widespread adult recognition. Much of what we have, in this era of hell growing pains, is an attempt to link every possible health problem to autism, combined with a lot of questionable definitions (“in summary, autistic people use their highly developed and sensitive social skills to effortlessly mask their autism in all situations, which is why so few people in $speaker’s_preferred_demographic are diagnosed”). This lurks beneath, huge and undeniable. Yet we have no idea what it is.

What is it?

This is not exactly, completely comparable — Croen is studying all schizospectrum diagnoses, while Lo is specific to schizophrenia — but that’s another post, and I’m trying hard here not to let this overtake this post.

My running favourite example of this is “autism and STDs”. Is autism a risk factor for STDs? Blatantly no, in that it’s not a particularly good risk factor for…sex. (This is not “autistic people are asexual” or “autistic people never get laid”, which are both flatly wrong, but autistic people are nonetheless somewhat less likely to be sexually active, and in particular to be active with many partners.) Can you find evidence that autism is a risk factor for STDs? If you try hard enough. Can you publish that evidence? Sadly, yes.

Some studies (including the cited) suggest that 1. gait atypicalities are more common in “low-functioning autism” than “high-functioning”, thus 2. LFA is more “core” or “centrally” autistic than HFA. I’m skeptical about this conflation. There is definitely a “true LFA”, but traits that are autistic in other populations can be “developmentally normal” in severely disabled people (e.g. some amount of stimming/repetitive behaviour, poor understanding of social norms, unusual patterns of sensitivity and insensitivity), resulting in LFA overdiagnosis. All else equal, severely disabled people will have more atypical gaits than mildly disabled people, but this doesn’t always indicate the same disability. (There’s also the confounder of neuroleptics, which, again all else equal, people with LFA are more likely to take than people with HFA.)

Double-check this one, because I’ve seen people misread it before — “prefers outspokenness to tact” is a negative correlation!

In the very long run, “most” gets complicated. Contrary to the impression you get from scaremongering patient pamplets, more people than not will remit partially or completely from a schizospec psychosis. People whose diagnosis is specifically SZ tend to do worse, because the SZ diagnostic criteria includes both “functional decline” and “has been going on for several months”, but it’s still routine for people to do pretty well over 20-year horizons. In these long-term follow-ups, a decent chunk of people no longer take neuroleptics, and this tends to be associated with good outcome in ways that (given particular details) are probably not just “people who’d have a good outcome either way quit the drugs”.

As an aside, because this study is Finnish, the sample of people in the whole country who the researchers were certain had both definite schizospec psychosis and definite Parkinson’s (as opposed to drug-induced parkinsonisms — lol) is so small they could list them all in the paper! There are several fun things there — like the classic “SZ age of onset is later than you think”, and the guy who for some horrifying reason was being given clozapine for schizotypal PD — but one of the most fun is that there’s a guy unironically diagnosed with “simple schizophrenia”, a 20th-century diagnosis for…uh…who the hell knows. Depression? Schizotypy? Dementia? Particular strains of hebephrenia? Hell, autism?

You can present them as “burnout” — positive symptoms come from an overdose of dopamine, negative symptoms come from dopamine production crashing back down. This seems to be fairly common 101 catechism, and it looks how drug abuse looks, which makes it an intuitive comparison (especially because so many people with drug-induced psychosis get diagnosed with functional psychosis). It would be a great hypothesis if negative symptoms actually worked that way, i.e. you developed them after having positive symptoms for a while without treatment. Reality is closer to the opposite — they start earlier, persist, and don’t respond to conventional SZ treatment. The other major hypothesis is that they’re about high or low dopamine in different brain regions, which I think is as-plausible-as-chemical-hypotheses-get, but certainly raises many questions about widespread long-term neuroleptic use.

Note that the second of these is “simple schizophrenia”. Wastebasket diagnoses, man.

Some autistic readers are probably looking at this and going “how can they be both polite and honest? Politeness is a way people avoid being honest!” Boy, that is not the way the other 95% think.

A lot of people talk about “HFA” and “LFA” in ways that imply those words…make sense, or were defined in some intuitive way — the whole sphere of what people think about when they think about “severity”, or the stereotypes that pop into their heads when they hear those terms. Nope! It’s a hard line at the intellectual disability border. Someone with an IQ just above has “high-functioning autism”, and someone with an IQ just below has “low-functioning autism”. This — and the things that spill out of it, like the questionable value of IQ in extremely neurodivergent populations in the first place — is where the problem with functioning terminology lies, not any of the complaints that tend to filter down to people.

There is a type of “HF”-autistic person who treats (their idea of) “LF”-autistic people as an outgroup. In the years between Starkstein and Geurts, I saw a lot of these people respond to Starkstein in a relatively blaise way — “well, those guys are nothing like me, so why should I care?” Let it be remembered: these are your brothers-in-arms.

This is roughly equivalent to the DSM-IV era, where you have a trimodal “autistic disorder” (with both “HFA” and “LFA” variants), “Asperger’s syndrome” (“disorder” rather than “syndrome” in the ICD), and something variously called “atypical autism” or “PDD-NOS”. People tend to talk about this in a bizarrely nostalgic way, because they mentally round Asperger’s to all “high-functioning autism” and ingroup it as a Totally Different, Better Thing. The intensely wacky mess that was Asperger’s should be its own post, but this is…something of a simplification of reality.

The most common diagnosis in this era, consistently, across the whole spectrum, was “atypical/PDD-NOS”. Everyone with PDD-NOS got grandfathered when the DSM-5 moved to lumping, but many of those people wouldn’t actually fit DSM-5 autism spectrum disorder criteria as written. In practice, of the people I’ve met who say or allude that they were diagnosed with PDD-NOS, they’re all pretty clearly autistic in a colloquial sense. “People I’ve met” is doing some work here.

“Negative correlation between autism and cancer” is one of those funny things. It’s hard to study, because the effect is a lot smaller than things like the parkinsonisms effect, and because autism diagnosis is a mess and the worst thing ever. Research in large diagnosed samples suggests a spurious positive correlation — that is, “people diagnosed with autism” are slightly more likely to get cancer young, but this disappears when you remove “complex autism”, i.e. autism diagnosed in the presence of identifiable birth defects or genetic syndromes. I think most (not all) complex autism is misdiagnosis/diagnostic substitution. Even in the case of “real” autism comorbid with one of those things…well, I’d be more inclined to ascribe the cancer to the genetic syndrome than the autism. Since such a large share of diagnosed-autism is “complex” (at least 20%), it’s a huge pain to draw conclusions about weird small effects. Yes, this is a huge pain for the parkinsonisms thing too.

Some autistic people under 65 are eligible for Medicare, as it’s also for people who receive Social Security disability benefits, but Hand et al. (2020) only looked at enrollees aged 65+.

You run into a type of person who is self- or other-diagnosed schizoid, who is pretty sure they’re schizoid — something they understand as, roughly, “weirdo introvert” — and absolutely certain they are not autistic. This is a tad inconvenient for them, given they’re the same picture. The distinction people try to draw when they try to draw a distinction is approximately “schizoid people aren’t as bad at social skills as autistic people”, which one may suggest is a little subjective. At least one person I’ve met who did this later discovered he was diagnosed with autism as a child.

(“Ever? That’s a big question! Well, better think about all the times my legs felt stiff. If I recall correctly, once was the 16th of June, 1994…”

That is totally how I would interpret that question.

Catching up on my backlog, just read this.

Despite the complexity and length of the post your writing remains very engaging throughout, it was a pleasure to read, thanks for writing it :)