Disorganized Schizotypy and the Problem of Measures

the map is not the territory, but what is personality's territory?

Is Traumatic Brain Injury “Caused By Genes”? has Done Numbers, because it turns out being mentioned in a linkpost of one of the most-read Substacks gets you a view count boost, even if you’re buried in the middle of the list between several political articles that everyone is yelling about in the comments. Shocking, I know. (Hi to everyone who subscribed from that!)

I’ve been thinking about the discussion between myself and Scott in the comments that revolved around disorganized schizotypy. To generally recap, schizotypy is something like this:

It’s a lifelong set of personality and developmental traits that are more common in people who have psychotic episodes (chronic or otherwise), and in people with a family history of such, but most schizotypal people never develop a “psychotic disorder”, and not all people who do are extremely schizotypal

It is (from where I’m standing) clearly the core element of the schizospectrum, in the same sense autism is not defined by “the most severe autism” and “all other people on the planet”, but tends to be underresearched and mostly considered as a psychosis prodrome rather than its own thing

Because schizophrenia is conceptualized in terms of “positive symptoms” (delusions, hallucinations, thought disorder) and “negative symptoms” (anhedonia, withdrawal, apathy), schizotypy tends to be conceptualized as “positive schizotypy” (subclinical positive-symptom-spectrum experiences) and “negative schizotypy (a grab-bag of introversion- and anhedonia-related factors)

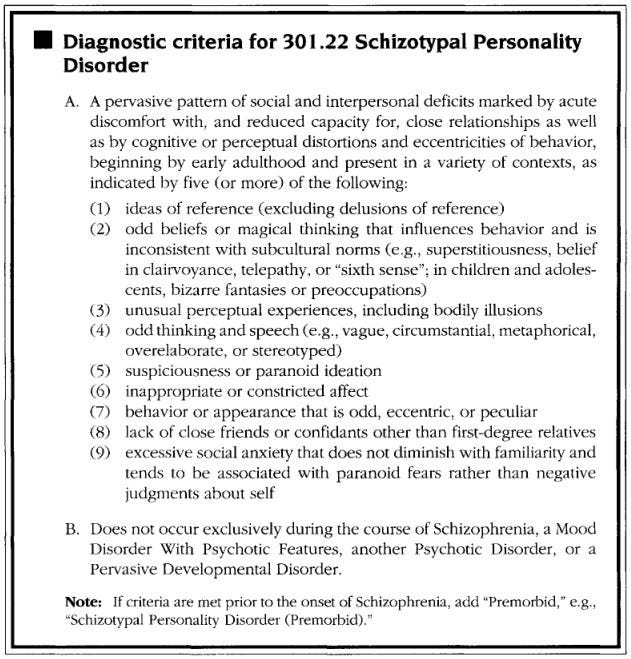

This is what schizotypal personality disorder, the diagnostic category for very schizotypal people, is described as in the DSM:

(A lot of people look at this and go “huh, it sure is…a thing that this is a diagnostic category inherently marked as deviant/wrong, isn’t it?”. To which: yeah. Yeah, it sure is a thing.)

Because schizotypy isn’t schizophrenia, the classical “positive/negative” distinction gets a little tricky. Some things on this list map to one or the other; “odd beliefs or magical thinking” are clearly-enough positive-of-centre, and “lack of close friends” is clearly-enough negative-of-centre. Others seem to jump around.

Some forms of schizotypy seem more “core” than others, in that they correlate better with having other kinds of schizotypy, with potentially having a psychotic episode, with having a family history of psychosis, etc. This is often expressed as “negative schizotypy”, in particular, being more central to the construct. Some small, minor problems arise when you look at what gets called negative:

I know that when I think of negative schizotypy, “suspiciousness or paranoid ideation” is the first thing that comes to mind!

You might also notice that “odd speech and behaviour” lands in “negative”. Schizotypy scales have a strangely hard time accommodating this cluster. Intuitively, it’s clearly positive. For instance, it’s a positive thing to have — oh wait, I’m supposed to pretend “positive” and “negative” have some unique term-of-art meaning still? Fine. It’s clearly positive, in that the term-of-art meaning (“having things other people don’t have” versus “not having things other people have”) will generally put them in the “having things other people don’t have” cluster.

But the scales we use to measure schizotypy put it all sorts of places, and never seem to come up with “two separate clusters” in the first place. The most famous schizotypy scale is the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire, designed by psychologist Adrian Raine in the early Nineties and available for free on his site. The SPQ has a three-factor model, working out as “Cognitive-Perceptual” (positive), “Interpersonal” (negative), and “Disorganized”, which comprises oddness. Hey, we didn’t mention disorganized before, didn’t we?

“Schizophrenia” is not a homogeneous morass of “crazy people, I guess”. People labelled with that term have always been as different from one another as anyone else. The DSM-5 goes hard lumper, but every prior DSM (and pre-11 ICD) is convinced “schizophrenia” forms multiple clusters.

The famous one is paranoid schizophrenia, which practically serves as a metonym for all SZ in popular culture. Classically defined, paranoid schizophrenia is relatively late-onset (usually after 25, often after 30),1 characterized by delusions and hallucinations with few other aspects, and tends to present an acute onset and relapsing-remitting course. Paranoid schizophrenia informs many psychosis stereotypes, and the name really rolls off the tongue, but it’s not the only one.

The counterpart was disorganized schizophrenia — hebephrenia, if the paper you’re reading is real old. No one can perfectly agree on the distinction, probably because the distinction is bullshit and doesn’t exist, but there are trends:

Rather than the impossible lucidity of classic paranoia, classic disorganization is marked by thought disorder. Thought disorder is a concept I’ve always had something of a problem with. For one, obviously, hell of a statement to declare someone’s internal monologue disordered. But pushing aside the revoluciulo who lurks barely beneath my skin, and playing the game by its rules: thought disorder, definitionally, must be identified through someone’s speech. Given the fairly broad range in how people talk in the first place, and the complexities involved in translating thought to speech, this introduces a huge margin of error.

Nonetheless, one can talk about “thought disorders”. The classic form is “word salad”, the complete collapse of any observer-identifiable communication. We tend to use “word salad” colloquially to refer to pretty much any thought disorder, but term-of-art, it’s the furthest extreme (Wikipedia’s example: “Because it makes a twirl in life, my box is broken help me blue elephant”). Most thought disorder is more subtle and bears less resemblance to 2006-random-humour. Sometimes words are linked by their sound or aesthetic rather than their meaning, with conversations derailed by strange rhymes and topic jumps. Sometimes the train of thought derails halfway through, with a conversation coming to a full stop or meandering through very different ideas. Sometimes nothing can be excluded, every detail must be addressed, and a simple reply has to go through every possible circumstance before answering the question — if it ever does.

“Disorganized schizophrenia” might be more evocatively called “bizarre schizophrenia”. It is marked by a fundamental strangeness in someone’s speech and behaviour. Facial expressions and body language tend to be absent, inappropriate, or jumping rapidly between both. Habits become decidedly unusual; the archetypal “homeless bag lady collecting garbage” tracks closer to disorganized than paranoid SZ. Delusions are still typical, but they’re different — they tend to be “bizarre”, a term of art for delusions that can’t happen in what other people think of as “the real world” (consider the distinction between “the CIA are putting cameras in my home” and “the cyborg aliens replaced all my internal organs with cameras”). These delusions tend to be more “fragmented”, to not fit together in a coherent whole, as opposed to the “systematized” delusions of paranoia.

To be clear, textbook distinctions crash and burn upon exposure to reality. There are reasons DSM-5 killed the subtypes, and it’s not just that DSM-5 is aggressively lumper. Still, at the two hypothetical poles of “most paranoid” and “most disorganized”, you can see how the patterns shake out.2

Because the subtypes are fake, no one quite agreed on what “disorganized schizophrenia” should represent. It was not-infrequently referred to as “schizophrenia characterized by negative symptoms”. This was its own semi-mythical subtype, “simple schizophrenia”, which gets to go down as one of those horrible 20th century categories. Simple schizophrenia was a nightmare outgrowth of the neurodegenerative hypothesis, in which some grab-bag of depression, early-onset dementia, prodromes for various things (including SZ itself), and ?miscellaneous? could all be understood as forms of schizophrenia. “Pure-negative-symptoms schizophrenia” is not actually a coherent idea, because negative symptoms are definitionally nonspecific; there has to be something else going on.

Paranoia and disorganization both load on what we clinically call “positive symptoms”, in that they’re both “things schizospec people experience and most people don’t”. Given schizotypy tends to be understood as loading on the same things schizophrenia does, “disorganized schizotypy” must exist as a concept alongside the other known schizotypies. What is disorganized schizotypy? That’s harder.

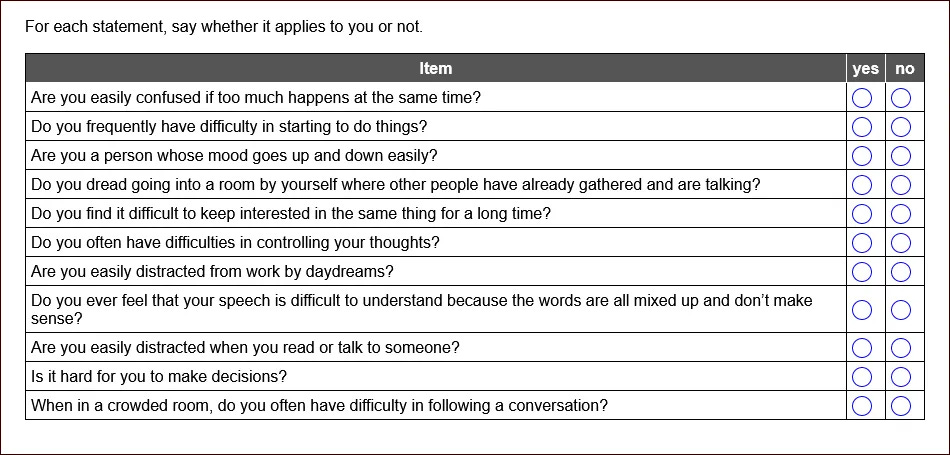

The SPQ lands on an “oddness” axis, but not every schizotypy scale finds the same “third cluster”. The Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE), another common scale, ends up with a four-factor model of “positive”, “negative”, “disorganized”, and “antisocial” schizotypy (it stands out to me that no one else believes the last one exists). Cognitive Disorganization correlates with all STPD criteria, but especially with “odd speech” (= thought disorder) and anxiety:

(“‘Negative schizotypy’ is not specific to schizotypes” stands out real hard here.)

What is Cognitive Disorganization picking up on? Good question.

Several of these sound reasonably like they pick up on a schizotypy signal (difficulty controlling thoughts, intense daydreaming, difficulty making oneself understood). Others are nonspecific, and seem like their schizotypy signal is confounded by the many other reasons people are distractible and labile. It’s a bit of a mixed bag. (I notice that the three “unambiguously disorganized schizotypy” questions are the easiest yes answers for me.) In particular, I wonder if “the questions that correlate well with odd speech” and “the questions that correlate well with anxiety” are different questions.

Still, those are pretty solid correlations, all things considered. Cognitive Disorganization also seems to be the lowest scale in “healthy volunteer” samples — in Fonseca-Pedrero et al. (2015), it had a mean of only 1.5 (out of 11) on the short O-LIFE. Introvertive Anhedonia had a mean of 4.12! Getting a high score on Cognitive Disorganization seems linked to something meaningful.

The recent Multidimensional Schizotypy Scale aspired to build a better schizotypy measure — one not normed on a handful of Californian undergrads, say. (You’ll be surprised to hear the SPQ’s norms are too high!) Instead, it was normed on thousands of Midwestern and Southern undergrads, and also Mechanical Turk survey-takers, a highly representative and reliable population with normal rates of being schizospec — ah. Well, alright, it’s better than Californian undergrads. It also aimed to design a disorganized schizotypy measure that actually “target[s] disruptions in thought, organization, and communication” (Kwapil et al., 2018, p. 216), rather than the grab-bags of the SPQ and O-LIFE. It ended up with…an almost identical scale to O-LIFE Cogntitive Disorganization.

Nonetheless, there are enough “clearly picking up on it” questions for disorganized schizotypy to be a visible factor that correlates well with positive schizotypy and nearly as well with negative:

It even seems like it’s starting to get at the “core” of schizotypy, in a way positive and especially negative don’t. The O-LIFE has more consistent correlations with every STPD criterion, and the MSS bridges the relatively unconnected positive and negative scales. But you do notice that neuroticism correlation, don’t you?

In the OCEAN or Five-Factor Model — the undisputed winner of personality psychology — all personality traits can be simplified to Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. The simple cheatsheet is that Openness is the good one that measures all human value. Wait, it’s not? Goddammit.

Of these, Neuroticism tends to get the most play in clinical psych. It measures, rather indiscriminately, an array of traits people tend to understand as negative — things ranging from depression to anxiety to low impulse control to having a hell of a temper. It tends to be simplistically viewed as a Bad Thing, which is close enough for government work but fails hilariously when examined in e.g. measures of “willing to disregard social norms in useful and interesting ways”. We seem to be consistently bad at handling traits that let you do that! Wonder why.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Neuroticism is not especially fun, and its benefits, such as they are, coexist with its well-known propensity for misery. I wonder how many of the neuroticism-benefits are just artifacts of schizotypy.

Because there is some sort of association between schizotypy (including schizophrenia) and neuroticism. The stereotypical Big Five profile for people diagnosed with schizotypal personality disorder is “high neuroticism and openness, low everything else”. For people diagnosed with schizophrenia, it’s “high neuroticism, low everything else including openness”, which I — let’s put it this way — think is a good example of measurement error when applying tests to populations well outside their norms (Camisa et al., 2004). But neuroticism is presumably a risk factor for chronicity in psychological distress, and schizotypal PD as a diagnosis has “super anxious” right there in the criteria. Can we assume this is a constant?

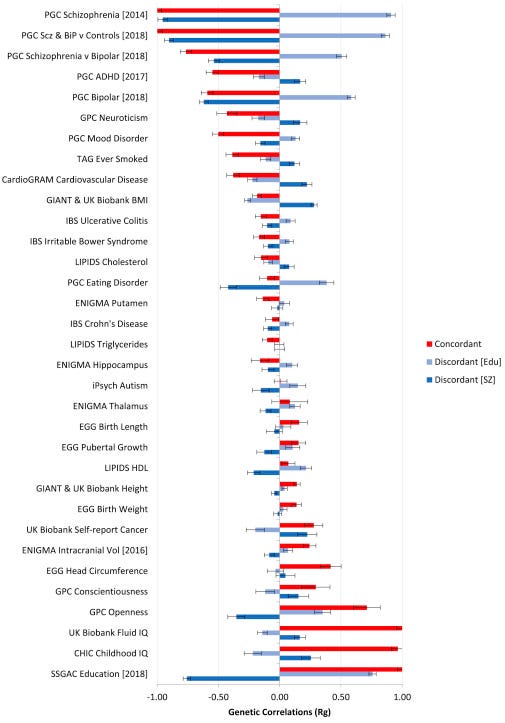

As previously discussed, “schizophrenia genes” represent “variants particularly common in people diagnosed with schizophrenia”, not “the obvious single-factor causes”. Because lots of people get diagnosed with schizophrenia, actually, there’s a lot of interesting variance in there. One particularly interesting point is that while there’s a weak negative correlation between “schizophrenia polygenic score” and “intelligence polygenic score”, there’s a weak positive correlation between “schizophrenia polygenic score” and “educational attainment polygenic score”. Intelligence PRS and education PRS are tightly intertwined, so you don’t see something like that every day.

Lam et al. (2019) decided to finally take this seriously and drill down into the associations. They identified and contrasted the following groups:

Variants associated with higher intelligence/educational attainment and lower SZ rate

Variants associated with higher intelligence and lower educational attainment/SZ rate

Variants associated with higher educational attainment/SZ rate and lower intelligence

It culminated in this chart, which you could write a whole post on:

I love this thing, it’s incredible. Negative correlation with cancer! Positive correlation with autism! Negative correlation with conscientiousness, the traditional explanation for disproportionate educational attainment, which produces the purest possible intellectual curiosity signal there is!

And oh, hey, neuroticism is a negative correlation. A weak one, but the error bars don’t touch zero.

This isn’t a disproof of an association, of course, nor is it trying to be. It does, however, suggest the assumption of a certain schizotypy-neuroticism correlation — the concept that something being associated with the schizospec means it must also boost neuroticism — is on shaky ground.

Building a psychometric scale is hard. Small decisions can have large impacts. Because schizotypy is clearly-but-not-universally associated with neuroticism, you need to prevent schizotypy tests from accidentally becoming neuroticism tests. The Multidimensional Schizotypy Scale made such an attempt; as a tiebreaker, negative schizotypy questions were more likely to be included if they had a low correlation with neuroticism, and positive/disorganized questions if they had a low to moderate correlation with neuroticism. Wait. Is that how schizotypy works?

“Negative schizotypy” picks up on a lot of things. Most of them are anhedonia, particularly social anhedonia (getting little enjoyment from social interactions). It correlates with pretty much every sort of psychological distress or atypicality, unlike the more specific signal of positive schizotypy. This is because it quite evidently is a proxy for every sort of psychological distress or atypicality. It corresponds well enough to the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and is associated enough with other schizotypies, to deserve a place in schizotypy scales — but you can’t take it too seriously by itself. It…doesn’t seem less neuroticism-associated than positive schizotypy, let’s put it that way. Studies on the SPQ and O-LIFE, which don’t have the MSS’s intentional and unequal dissociation from neuroticism, find comparable loadings in “healthy volunteer” samples (Ettinger et al., 2005; Premkumar et al., 2018; Völter et al., 2012). These presumably underestimate the correlation, for reasons we’ll get into later.

The MSS’s lower negative-neuroticism than positive-neuroticism correlation is artificial! There was, for whatever reason, a design decision to force the smallest association between negative schizotypy and neuroticism you could, while caring much less about the positive/disorganized associations. I can see reasons why you’d do this — positive and negative schizotypy are not-completely-terribly understood at this point, and we definitely understand the “negative schizotypy keeps picking up on every kind of neuroticism imaginable and not on a schizospec signal” part.

Then we launch into disorganized schizotypy, which we don’t understand at all, and — oh, there’s a .55 correlation. Hm. The MSS isn’t alone here. The full-length O-LIFE, which expands on the short version’s disorganization scale by adding even more “do you have anxiety?” questions, has a correlation that starts looking like the g-factor. So either disorganized schizotypy has to be way more associated with neuroticism than anything else, or we still haven’t figured out how to measure it.

Permit me to make the case for Lived Experience.

I am clearly a schizotype, though I don’t tend to label it in much more detail. (To do so would be to take this post too far off-track.) I’ve known both “paranoid” and “bizarre” phenomena. I’ve seen them, psychotic or not, in quite a lot of people.

There is no way in Hell “mild thought disorder” is more connected to neuroticism than any other kind of schizotypy. The parts of schizotypy that shade furthest into neuroticism — moodiness or tenseness or knife-sharp anxiety — aren’t that part.

In fact, none of our disorganized schizotypy scales seem to measure “mild thought disorder”. They are, it seems, conceptualizing it from the outside. Thought disorder is tricky. People tend to perceive it through its most extreme presentations, and often don’t seem to realize it can be mild at all. When you have to get into the nitty-gritty process of constructing a measure for it it, it becomes clear how subjective the concept is, and exactly what calling someone’s internal monologue “thought disorder” implies about both them and you.

The Multidimensional Schizotypy Scale’s disorganization questions include:

“My thoughts almost always seem fuzzy and hazy.”

“My thoughts are so hazy and unclear that I wish that I could just reach up and put them into place.”

“I often struggle to stay organized enough to complete simple tasks throughout the day.”

“I often feel so mixed up that I have difficulty functioning.”

The latter two are “Well, yeah, you’re getting a signal there, but it’s sure not a disorganized-schizotypy-exclusive signal” (psychometricians design a scale that isn’t just ADHD challenge). But the former two are fascinating to me, because there’s an assumption underlying them that isn’t how it works.

Extreme thought disorder is impossible to describe for much the same reasons psychedelic thought is, but “fuzzy and hazy” is wrong for much the same reasons it would be for psychedelics. Disorganized thoughts are twisting, curling, abstract, implausible, sidetracked, atracked, posttracked, jumping and botching the landing — but they’re not hazy.

The other interesting assumption is that disorganized thoughts are consistently ego-dystonic. People tend to like having their neurotypes and thinking the way they think. The MSS isn’t the only scale I’ve seen cause problems by making this error. One IDRlabs test offers the question “My thoughts have a tendency to run in strange loops and dwell on weird themes, and I wish I could get rid of this”. People who are certain yes answers to the former — who are very high in disorganized schizotypy — usually don’t want to get rid of it! (The description is, however, more accurate than anything on the MSS.)

Any disorganized schizotypy scale that makes these errors is picking up on something atypical of disorganized schizotypy. I suspect it’s “people norm the schizospec on its most extreme and dysfunctional forms” bleeding through. The most pronounced possible manifestations of thought disorder can be distressing, and psychotic episodes in retrospect are hard to remember or introspect well, but this is a small and not especially representative minority of schizotypes.

Tongue-in-cheek: a truly accurate disorganized schizotypy scale probably wouldn’t ask about “problems with how you think” at all. “For some inexplicable reason, probably their fault, other people don’t understand me.” There’s a good question!

So what are our disorganized schizotypy scales measuring?

To rehash, this is the short O-LIFE (which manages to have a better signal-noise ratio than the full version):

A couple of these are clearly anxiety. There are lots of reasons to be anxious, including reasons that route through schizotypy, but nothing here is specific.

Some are all-purpose distractibility. I think this is another “seeing the schizospec from the outside” problem. People in disorganized psychotic episodes come across as very distractible, but are a small minority of all distractible people, and you’re mostly identifying “below-average concentration ability”. The experience of thought disorder mostly doesn’t seem, internally, like being unusually distractible. It is from an outside perspective, because most people are not very paracosmic and interpret paracosms as distractions, but it can’t be relied on as the term that first comes to mind. (“What do you mean, easily distracted? I’ve been focusing on my thoughts for hours!”)

Some are…sigh. I’m pretty sure the O-LIFE and MSS are at least partially picking up cognitive ability, not disorganized schizotypy.

Because schizotypy is seen through the lens of schizophrenia, rather than the other way around, assumptions from the latter tend to be carried into the former. The most extreme end of the schizospec — severe, poor-prognosis, chronic psychosis — is negatively correlated with intelligence. Through the clinician’s illusion, this colours most practitioners’ views of both schizospec psychosis and the schizospec at all; people who remit quickly from psychosis or never experience it don’t spend much time in the clinic. The furthest disorganized pole, of disorganized/bizarre schizophrenia with fragmentary and incoherent delusions, has a particularly strong negative correlation (Kremen et al., 1994);3 allow me to suggest many reasons why people with heavy thought disorder would get low scores on cognitive tests independent of intellectual ability, but the real effect is probably not zero.

Schizotypy scales, accordingly, end up filled with “are you easily confused” and “do you have trouble understanding what people say” questions. Those are things that can be related to thought disorder, yes. But schizotypal people are not super common, and people with below-average cognitive ability are, definitionally, half the population. Congratulations on your finely tuned instrument for detecting anxiety disorders in people of below-average intelligence.

Not only does this disrupt research on schizotypy for its own sake, it even disrupts the “schizophrenia risk” research people narrow in on. Velocardiofacial syndrome is a common-if-you’re-normed-on-genetic-disorders microdeletion syndrome with a ~30% lifetime rate of presumed-schizospec psychosis, which you might recognize as “higher than the rate in monozygotic twins, what the hell”. I am seeking funding for research on it (pls fund). There is barely any research on schizotypy in VCFS, and a little more on “prodromal psychosis”, which uses similar scales to schizotypy.

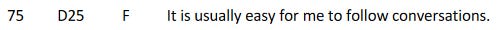

The evidence that people with VCFS have elevated positive schizotypy is, uh, noncommittal. The evidence for elevated negative schizotypy is better, in the sense that the Number Goes Up in the expected direction. But, uh, which number? The most commonly used instrument here is the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Symptoms, a common prodrome scale known for its not-at-all-evil insistence that “hav[ing] strong feelings or beliefs that are very important to you, about such things as religion, philosophy, or politics” is a herald of schizophrenia. Compared to other teenagers, or other maybe-schizospec teenagers, young people with VCFS consistently show up as elevated on “Decreased Ideational Richness”. This is “Decreased Ideational Richness”:

The average IQ of people with VCFS is around 75. Take your two groups of “maybe schizospec” kids, one with an average IQ of ~75, one of ~100. We’re positing it’s a difference in how schizospec they are if the former group have more difficulty understanding big words and interpreting proverbs?

I keep running into this problem when looking into “how might someone with VCFS respond to this scale”, or indeed “how might a control participant of matched IQ respond to this scale”. It’s important to actually understand schizotypy in VCFS, because we don’t, and the things we do understand (combined with other evidence) go down strange paths that may or may not resemble the schizospec as it exists elsewhere. Do we actually have a schizotypy measure that won’t crash and burn for someone with a borderline intellectual disability? More to the point — given how core it seems to the construct in even our imperfect, half-right measures — do we have a disorganized schizotypy measure that won’t?

Here’s the answer to “how can research on VCFS schizotypy impact more than 1 in 4000 people”! Trying to do it right will at some point require making an entire new disorganized schizotypy scale that actually measures disorganized schizotypy and not “are you distractible and easily confused”, which will work just as well for everyone else. pls fund

It’s not quite “the most dire thing in the known universe”. There are questions that get it right. We’re clearly getting some signal, and even in its distorted form it’s providing an important link between the weird and probably artificial positive-negative poles.4 But there’s way too much noise.

This is important, because even as much signal as we have implies “disorganized schizotypy” is something worth paying attention to. If there is a “core” schizotypy that plays a more important role than the others, it’s probably “mild thought disorder”, not “quasi-paranoia” or “introversion NOS”. If the concepts are bridgeable, it’s presumably what bridges them.

Schizotypy research in general is hard. This is one reason why. Another is the healthy volunteer problem.

For people who aren’t me and haven’t yet really digested the implications of the “neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia” (i.e. that talking about schizophrenia as the important part is like talking about all drug use as “traits associated with Overdose Disorder”), the main appeal of researching schizotypy is that you get to figure out some things about the schizospec without your sample being confounded by “everyone is horrifically traumatized by hospitalization and is taking drugs with physiologically and psychologically devastating effects”. This is to say it’s kind of inherently a “healthy volunteer” phenomenon — you want to screen out all the people who have a lot of prior contact with mental health or developmental disorder services. Is this actually compatible with studying a neurodivergent population in the year of our lord Current?

Let’s take “schizotypy is genetic and neurodevelopmental” seriously. Schizotypal people — including the minority who experience some sort of unambiguous psychosis, and the minority of that minority who develop a chronic positive and negative symptoms syndrome — are unusual from early childhood. They have a distinct, identifiable neurotype with pros and cons, not a nonspecific deficit pattern. They are recognizable as “weird” by their peers and by the adults around them. They likely come from families where this applies to quite a few members.

Weird kids these days can be called a lot of things — but for over thirty years running now, they’ve rarely been called nothing. A large share of the most schizotypal people will either have some sort of contact with psychiatric/developmental/behavioural fields or have relatives who did. Many “healthy schizotypy” studies have ridiculously high thresholds. The aforementioned Völter et al. (2012) excluded anyone with a first-degree relative diagnosed with ADHD!

How many people do you know who have absolutely no physical or mental health labels of any kind, would definitely still not have them by a gold-standard interview, take zero medications including multivitamins, and don’t have any relatives who have ever been diagnosed with the thing 10% of children are diagnosed with? More to the point, how many of those people would you think of as particularly schizotypal?

A lot of research fails to account for “schizotypes are weird, and have been weird their whole lives, and weird kids tend to pick up labels or have a family history of labelling”. I’m going to pick on one of my favourite/least favourite topics here: the “diametric model/imprinted brain hypothesis”, the claim that autism and schizotypy are fundamentally opposites by way of mumblemumble imprinted genes. It was devised in the late 2000s by Bernard Crespi (biologist) and Christopher Badcock (sociologist), whose ideas about it seem to have diverged somewhat in the intervening years. Crespi is doing actual research, while Badcock is doing this:

I have a real respect for Crespi, who is smart and inquisitive and doesn’t write for Psychology Today. I think he’s wrong, but better a wrong guy who has those characteristics than one who lacks them. Crespi has, I think, demonstrated reasonably well at this point that neurotypical undergrads in Western Canada tend to have above-average Autism Quotient or SPQ positive scores more often than both at once. I am willing to believe him that this is true, though when he gets into genes I am unenthused by his “drill down into subdivisions” practices.

Populations that are not neurotypical undergrads in Western Canada tend to, uh, not demonstrate this (see Dinsdale et al., 2013 — on which Crespi was corresponding author — for a very teeth-gritted literature review in the intro). Even in other undergrad populations Crespi’s anticorrelation is doubtful, particularly on non-SPQ instruments (Russell-Smith et al., 2011 is Dinsdale’s cite, but I’ve seen quite a few variants of this). Amongst people actually diagnosed with autism or schizotypal personality disorder, who seem like, you know, useful populations to study this in, there seems to be a there there (Barneveld et al., 2011; Esterberg et al., 2008). Outright psychosis definitely has a there there (Kiyono et al., 2020), and you keep running into hilarious studies that claim gold-standard ASD diagnostic instruments don’t work because they “misdiagnose” 30% of schizophrenics with autism (Maddox et al., 2017).5 Funniest of all, internet surveys find a large schizo-autistic population (Ford et al., 2018).

This suggests a problem with “healthy schizotypy” research. People who are very schizotypal and very autistic are even weirder than people who are one or the other, and particularly likely to be referred for psychological or developmental evaluations in childhood. They also presumably have more family history of one or the other, or of any of the labels people diagnosiswash to (e.g. ADHD in its “wastebasket for nonspecific childhood neurodivergence” role rather than its “pathologization of impulsivity” role).

I’ve focused on positive schizotypy here, because the SPQ’s disorganization is basically treated as positive by most observers, and because negative schizotypy has obvious overlap with autism that everyone recognizes. But these problems are likely even larger for negative schizotypy, which, when narrowly defined in its “introversion/anhedonia” cluster removing the role of thought disorder, ends up as part of everything. Even the very limited Goddamn Undergrad Samples we have show it as by far the aspect of schizotypy most associated with “problems” (Cohen et al., 2008; Horan et al., 2007).

Is disorganized schizotypy too weird to be easily detected in “healthy volunteers”?

People who think and talk in obviously unusual ways are “even weirder”, as a category, than people who are anhedonic introverts or magical thinkers. If — as seems quite clearly true — they bridge the two, this only amplifies the effect. Both “isolated negative schizotypy” and “isolated positive schizotypy” are comprehensible ideas that seem to exist (the former is pretty much all depressed people; the latter is the archetypal love-and-light New Ager). Someone with a lot of only disorganized schizotypy, in its truest form, is more difficult to picture. Anyone who fits that description is going to pick up unusual beliefs, an atypical way of emoting, etc. as a general consequence of navigating life as a disorganized schizotype.

They’re also less likely to make it to your “healthy volunteer” sample. The most obviously unusual subset of “all high-schizotypy” people are, definitionally, the most likely to end up raising developmental or behavioural concerns in childhood. By extension, they presumably have the strongest family histories.

Schizotypy scales are made for a broad population; they tend to exclude items that are endorsed by very few respondents. This is a problem when you, by definition, want to study traits most people don’t have. People with low-key thought disorder are rarer than people who are anxious or distractible or easily confused for other reasons. We end up with scales that are full of questions for the latter, but ask very little about true disorganized schizotypy.

Measuring this properly should also kill a lot of the neuroticism correlation. We keep filling disorganized schizotypy scales with questions about how you want to change your thoughts. Most people don’t want to change their thoughts!

Here is, approximately, how I understand schizotypy:

In a triad structure, “Strangeness” maps to Disorganized, “Magick” to Positive, and “Negativity” to, uh, Negative. The archetypal “schizotype” crosses all three categories; centrally they think, talk, and act in ways other people don’t, and this ~obligately leads to 1. being excluded from traditional social contexts and 2. holding, often strongly, uncommon opinions and beliefs.

Many things can grow from this. The furthest poles of Magick and Negativity are those that are most distinctly their own and least inherent to the core. For instance, magical thinking isn’t especially correlated with thought disorder, but it’s correlated enough. The furthest Magick item, “experience”, reflects fleeting and subclinical psychosis — which is caused by a lot of things, and correlates less well than you would expect with overall schizotypy. “Resignation”, the far end of Negativity, is the ultimately ego-syntonic total rejection of the outside world and its offerings; this is the classical “schizoid” profile, but not exceptionally common, and appears in a lot of not-overall-schizotypal people (some autistic people, some depressed people).

The problem with the “positive/negative” structure of schizotypy is that it’s based on a clinical impression of schizophrenia. You can talk about schizophrenia aspects that are “added on” to a neurotypical person’s experience (psychosis), and ones that are “removed” from it (anhedonia, avolition). You can talk about how this varies across someone’s life, how it differs between people, and how negative symptoms mysteriously look just like the effects of neuroleptics that everyone who takes them consistently reports. Schizotypal people are not schizophrenic, and do not in fact have a clear pattern of positive and negative symptoms.

In fact, schizotypy reveals just how the positive/negative symptoms distinction is a mirage. It’s clinically useful, and a reasonable introduction to the complexity of SZ, but it does not carve reality at the joints. It crashes and burns when exposed to thought disorder — which is a bit of a problem, given thought disorder is by every definition one of the core traits of schizophrenia.

At the extremes, thought disorder trades off on classical delusions and hallucinations. This is why “disorganized” schizotypy must inherently have a “positive” element — odd beliefs are “positive”, and any non-psychotic person whose thoughts sprawl and twist more than average will pick up some unconventional ideas on the way. Disorganized schizotypy without odd beliefs is the most extreme portrait of “disorganized schizophrenia”, where someone’s thoughts(/speech/behaviours) are so chaotic it’s impossible to describe them as “believing” anything or having any clear “delusions”. In anyone not at that furthest pole, they route back to being intimately connected; many elements of SZ (e.g. the classic Schneiderian first-rank symptoms) blend imperceptibly between thought disorder and delusion. Hallucinations, which are much more ‘obvious’ to most people as a schizospec characteristic, are surprisingly disconnected from this complex and pop up in all sorts of people for all sorts of reasons.

In turn, thought disorders run the entire “positive/negative” spectrum. Some thought disorders seemingly cluster with “negative symptoms” — feeling like your mind blanks in the middle of a sentence, or diminishing your speech to the barest minimum of words, or being unable to talk at all. This looks like a “negative symptom”, so the experiences closest to it become part of “negative schizotypy”. From here we also land in unusual affect (e.g. different or limited facial expressions), and in the classic double empathy problem of being mutually unable to understand the people around you.

As you go further out into the distinct Magick/Negativity corners, the association with central Strangeness weakens. This is why you can construct “positive and negative” scales that only weakly correlate in a general population sample. In more schizotypal samples (e.g. members of multiplex SZ families), the correlation ramps up, and the disorganization signal becomes strong enough to drag all sorts of weird things in with it if you somehow throw it in “negative”.

So all you have to do now is solve the problem that few people will endorse actual-disorganized-schizotypy questions, and solve the problem that “mild thought disorder” is a hell of a construct and inherently involves pathologizing someone’s Soul, and you’ve finally made a usable schizotypy measure! Yay.

It turns out constructing measures for “how do extremely unusual people perceive the world” is hard, especially when no such people were involved in the measure’s creation. “There is no moral to this story.”

postscript: hypothetical ideas for a useful measure

There are useful ideas in a lot of current measures. The “strange loops and weird ideas” question would be perfect if it didn’t include the second clause. A lot of stuff on the SPQ, O-LIFE, and MSS is genuinely useful.

Some items that should hopefully measure true disorganization and be endorsed by more than zero people:

“My thoughts often run in strange loops and dwell on weird ideas.”

“When I try to control my thoughts, I struggle at it.”

“I have intense and vivid daydreams.”

“Other people have a hard time understanding what I say.”

“No matter how hard I try, I sometimes can’t get someone to understand what I’m talking about.”

“People tell me my speech and ideas seem confused or difficult to follow.”

“Even when I want to pay attention to what’s in front of me, I often can’t stop daydreaming or thinking.”

“I feel like my thoughts are more complex or meaningful than other peoples’.”

“Sometimes I feel trapped in disturbing or terrifying thoughts.”

“People tell me I have a hard time getting to the point when I talk.”

“I have tried to say one thing and said a different thing entirely.”

“When I write an essay or give a speech, it tends to change topic partway through.”

“People tell me I derail conversations or change the topic too often.”

“It seems like I think in a fundamentally different way to everyone else.”

“My thoughts sometimes seem distorted, incoherent, or bizarre.”

“Sometimes, the sound or feeling of a word is more important to me than its meaning.”

“My inner world seems more intense or real than other peoples’ inner worlds apparently are.”

“Sometimes when I’m talking, my mind goes blank and I forget what I was talking about.”

“People tell me the way I act or the things that interest me are bizarre.”

“I feel like the things I say don’t make sense and don’t reflect my thoughts.”

Some of these are probably bad, but at least they’d be bad in new and interesting ways. In theory, they shouldn’t just be anxiety/distractibility/cognition measures, and should be a lot less of a neuroticism proxy.

"But I thought SZ age of onset was usually late teens or early twenties?” You would think that, and you would be wrong! The error bars on AOO are hilariously wide, especially for women. It’s not even called “late-onset” until you’re over 45. Yes, this does mean studies that use people in their thirties or even late twenties as “definite controls” are worthless, thank you for asking.

In the real world, “undifferentiated schizophrenia” (neither clearly paranoid nor clearly disorganized) seemed to be the majority or plurality diagnosis. The DSM-5 really clamped down on “not otherwise specified” categories, because people love picking “none of the above” for their special and unique situations, and because they all grow into horrifying wastebaskets that comprise everything that might look a little like the original idea, if you squint. Similar note: for all people yell about Asperger’s, “PDD-NOS” was just under 50% of all ASD diagnoses under DSM-IV.

I’m making this particular claim and citing this particular source because it highlights something useful. Kremen didn’t distinguish his groups by “paranoid/nonparanoid”, as is traditional, but “systematized/unsystematized”. This landed him with groups of “systematized delusions, little disorganization” (diagnosed paranoid), “systematized delusions, prominent disorganization” (diagnosed nonparanoid), and “fragmentary or nonexistent delusions, prominent disorganization” (diagnosed nonparanoid). Most studies just looked at diagnosis and found that nonparanoid (disorganized or undifferentiated) schizophrenia had more cognitive involvement, but Kremen found the systematization — the connected web of delusions forming a single idea — was the relevant axis, and that nonparanoid SZ with systematized delusions looks like paranoid SZ. Delusions are nastily understudied, because the mainstream view at present sees them as something to “treat” and forget about, but “what people care about and why” is in fact as important in atypical populations as typical ones.

Well, hopefully! It could literally just be neuroticism. But I think the low average score on the short O-LIFE compared with it having some good questions implies something is working, and later in this piece I expand on why I think that.

I’m being a teensy bit unfair here. Maddox is correct that autistic traits in SZ are messy and can be influenced by the onset and course of SZ itself, independent of pre-existing autism. In practice, though, explanations of why the coexistence isn’t real tend to sound something like “he had friends as a kid, so isn’t autistic”. One particularly…interesting…case study about “false positives” for autism in childhood-onset schizophrenia revolved around a kid who was first referred for evaluation because he only played by lining up objects. I think that might be a bigger signal than “having friends”!

A bit tangential, but for the longest time I've had a lexical gap for 'the personality trait which psychoticism sounds like it should mean but doesn't'; I'm pleased to learn there's an actual word I can use!

One of the things that always strikes me with questions about how you think or perceive the world is that most people have no comparison point - and to the extent that one can kind of compare with other people, the nature of bubbles mean that you won't ever be comparing yourself to an "average" person - your family shares your genes and your friends are probably actively selected for being "like you" in some way.

How rich is an inner world, 'normally'? How complex and meaningful are other people's thoughts?